Background

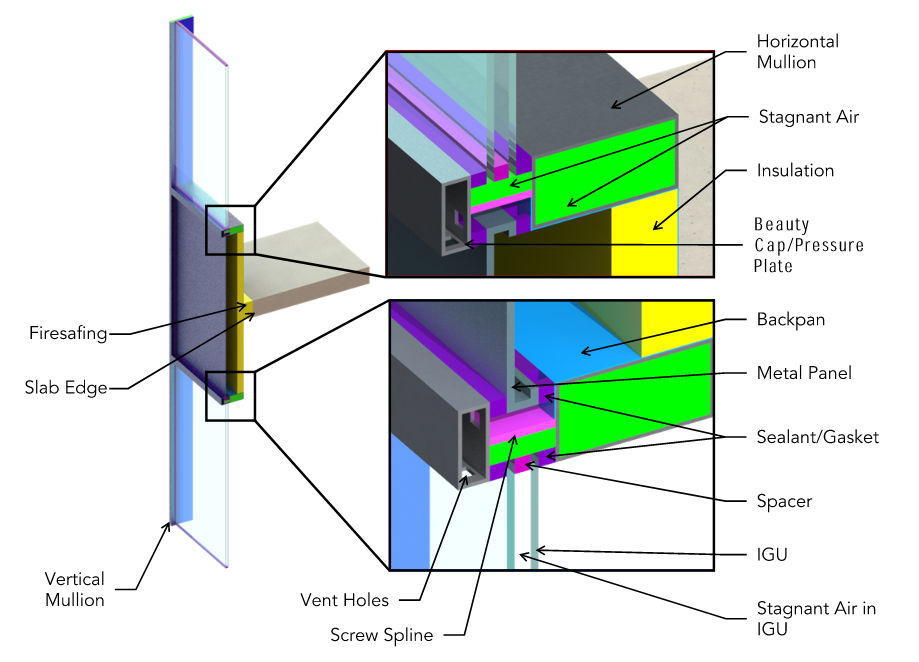

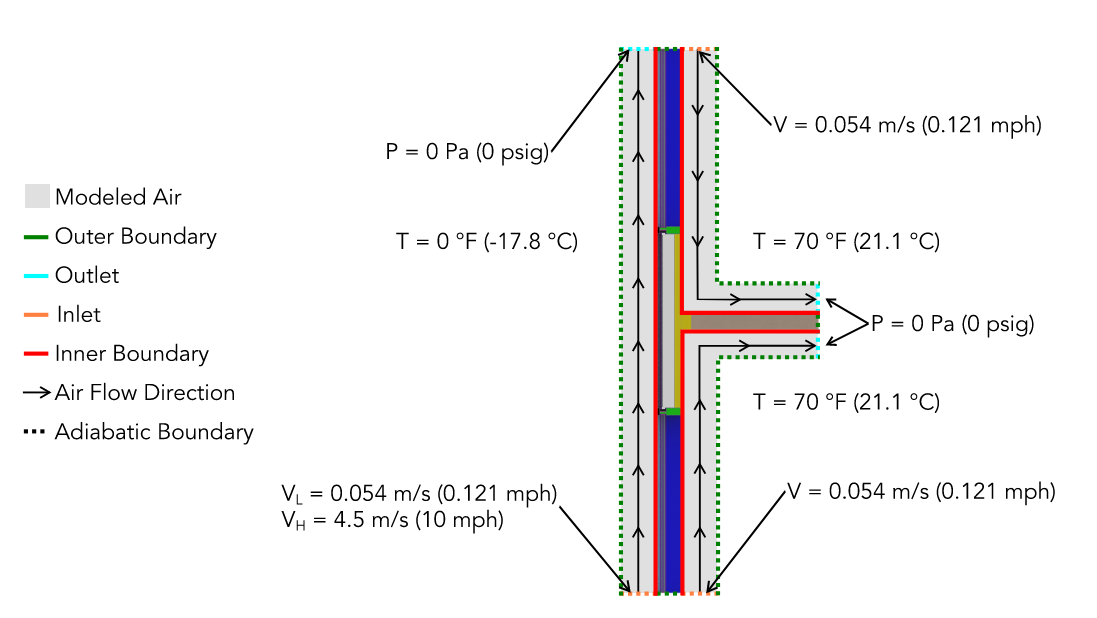

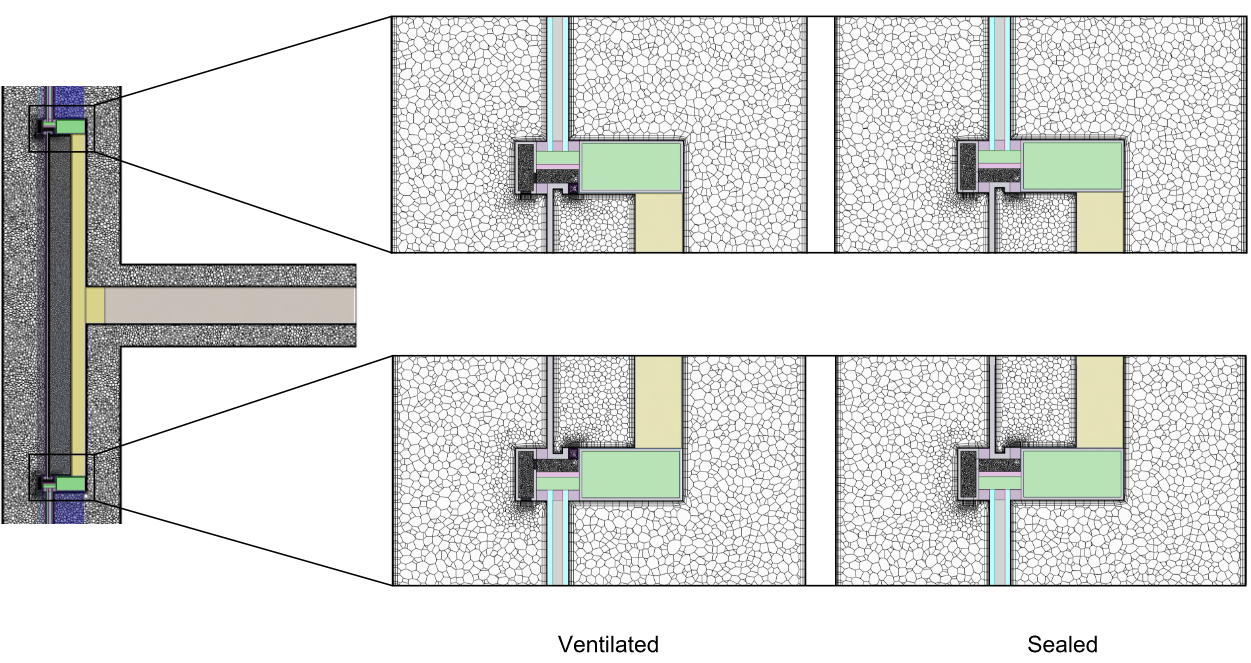

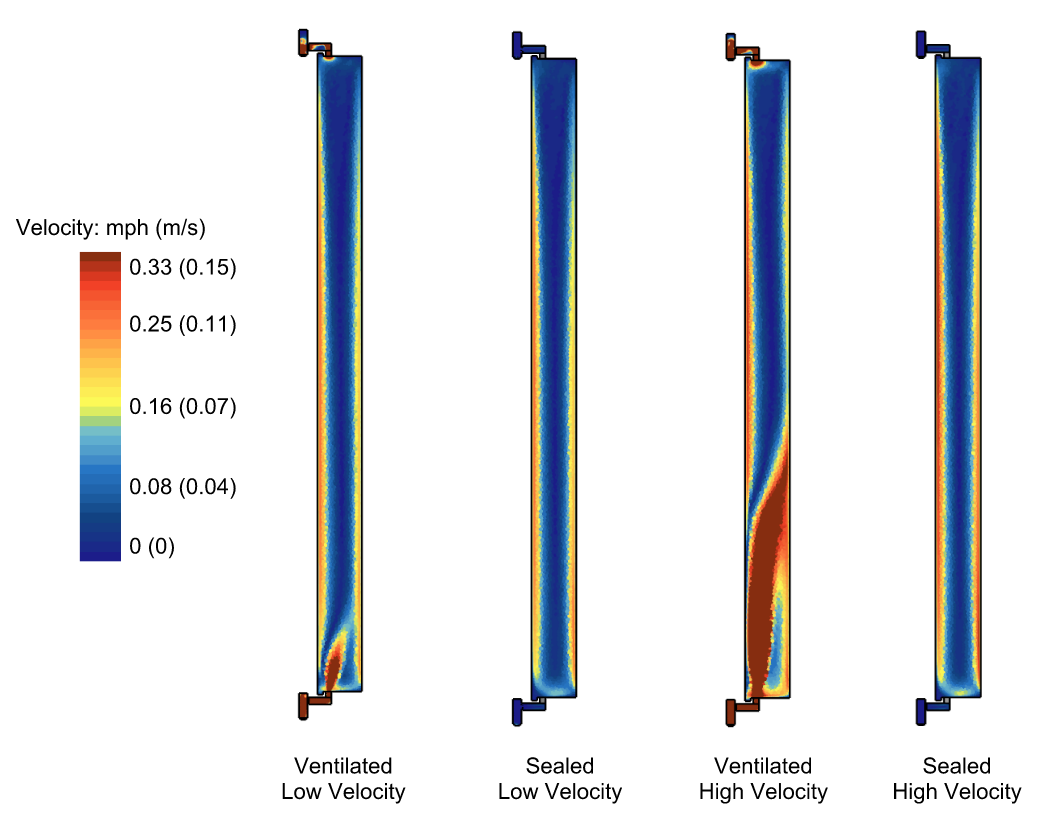

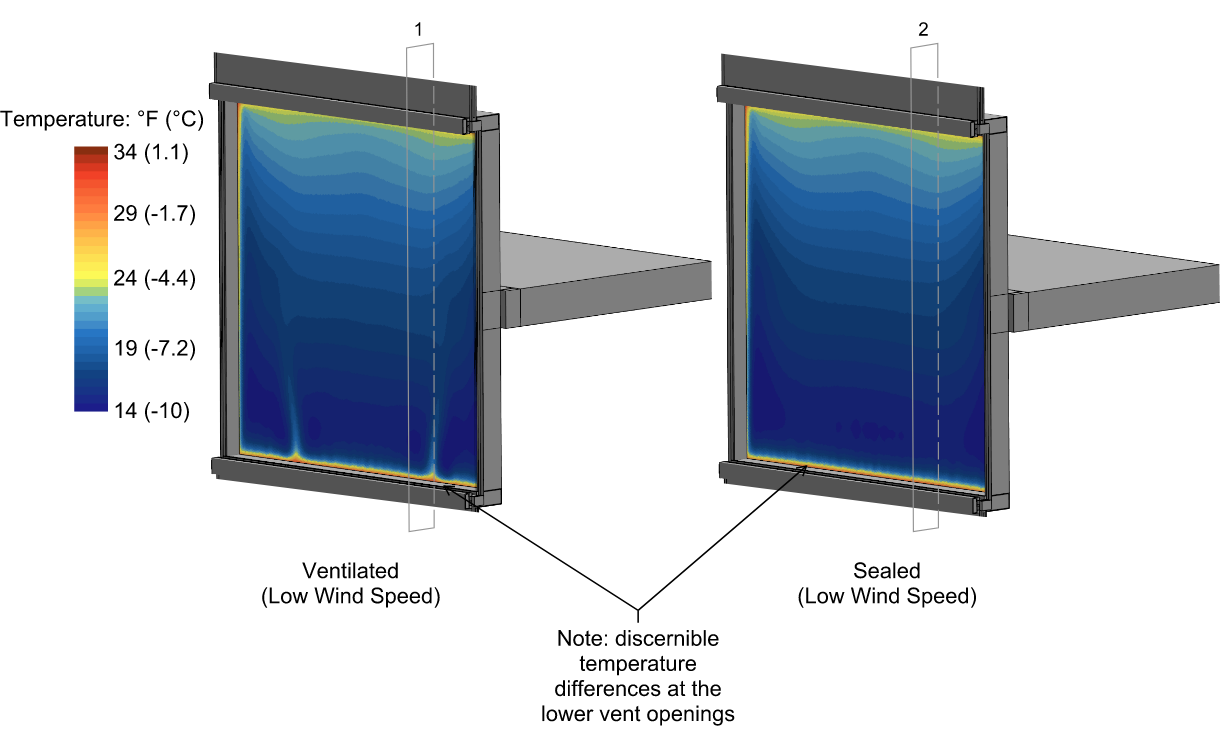

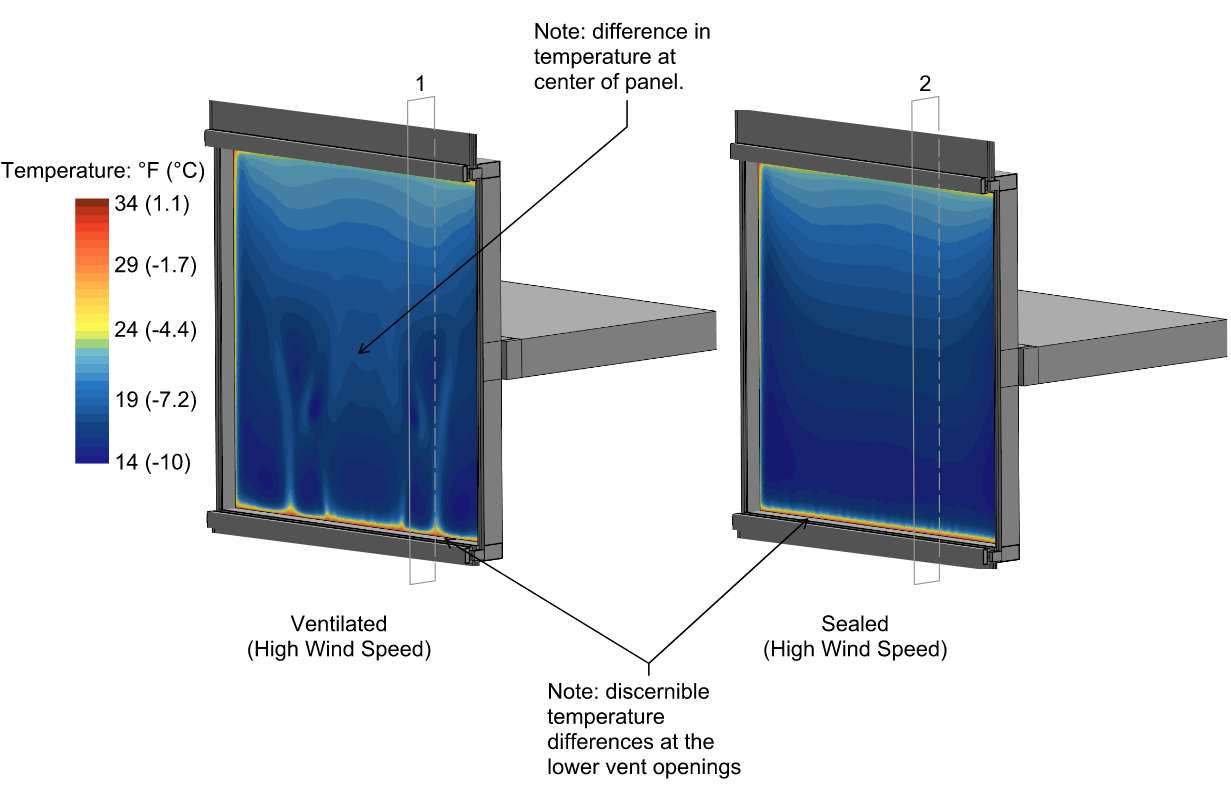

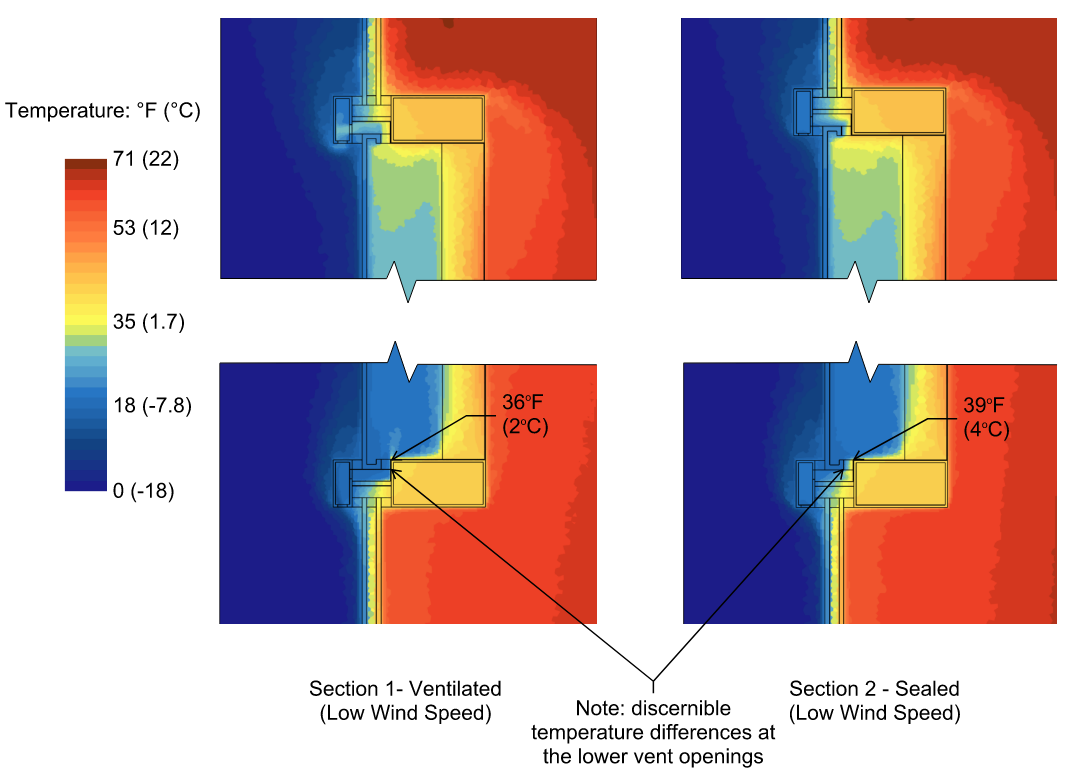

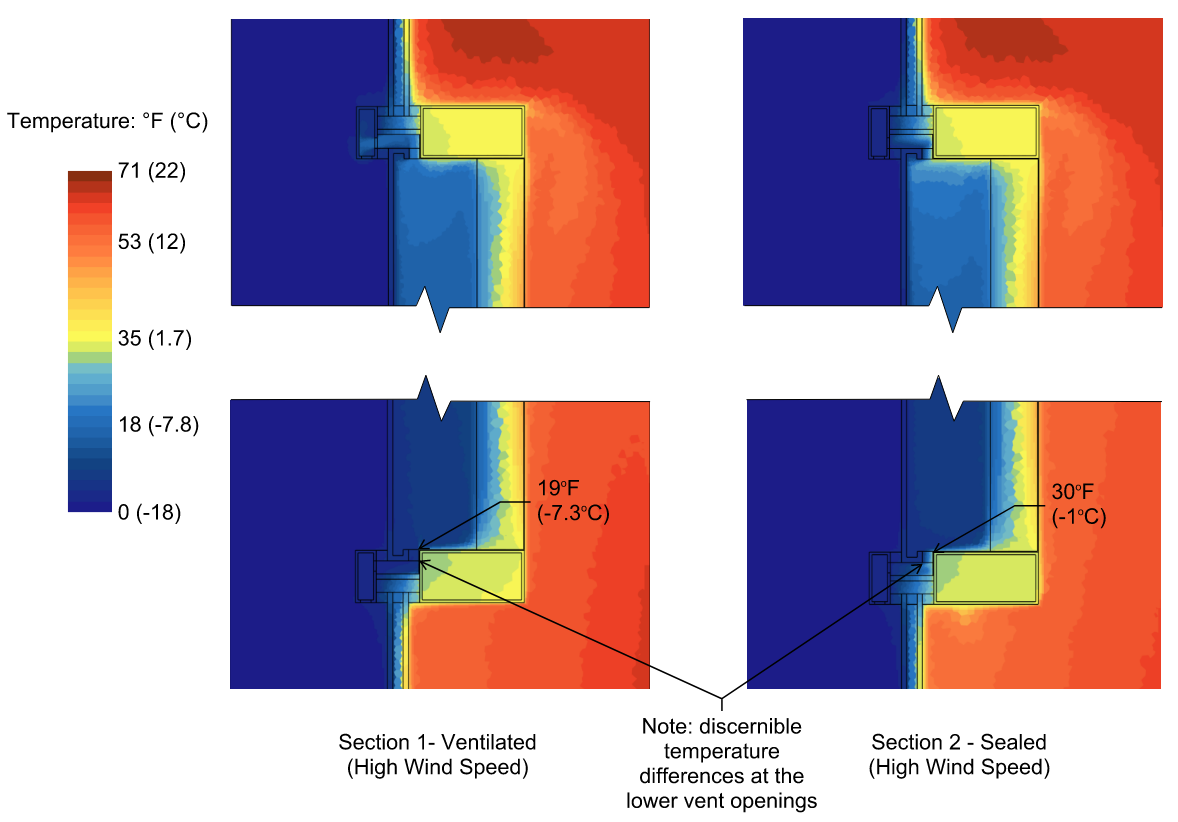

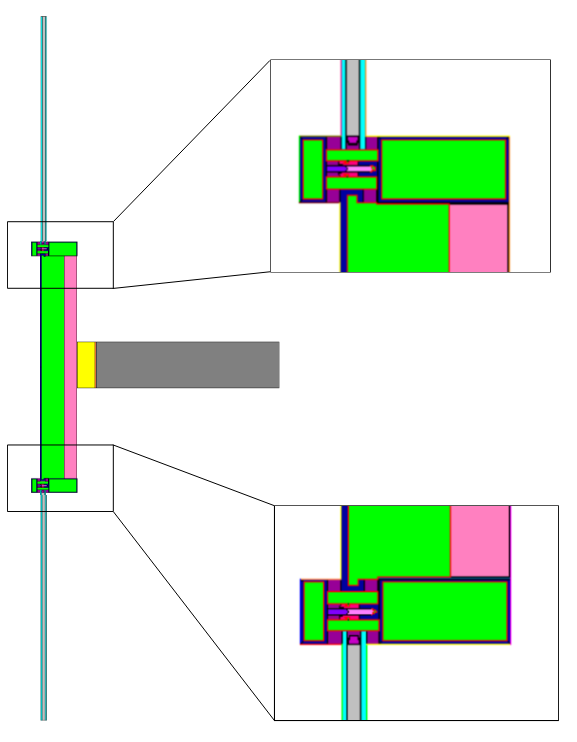

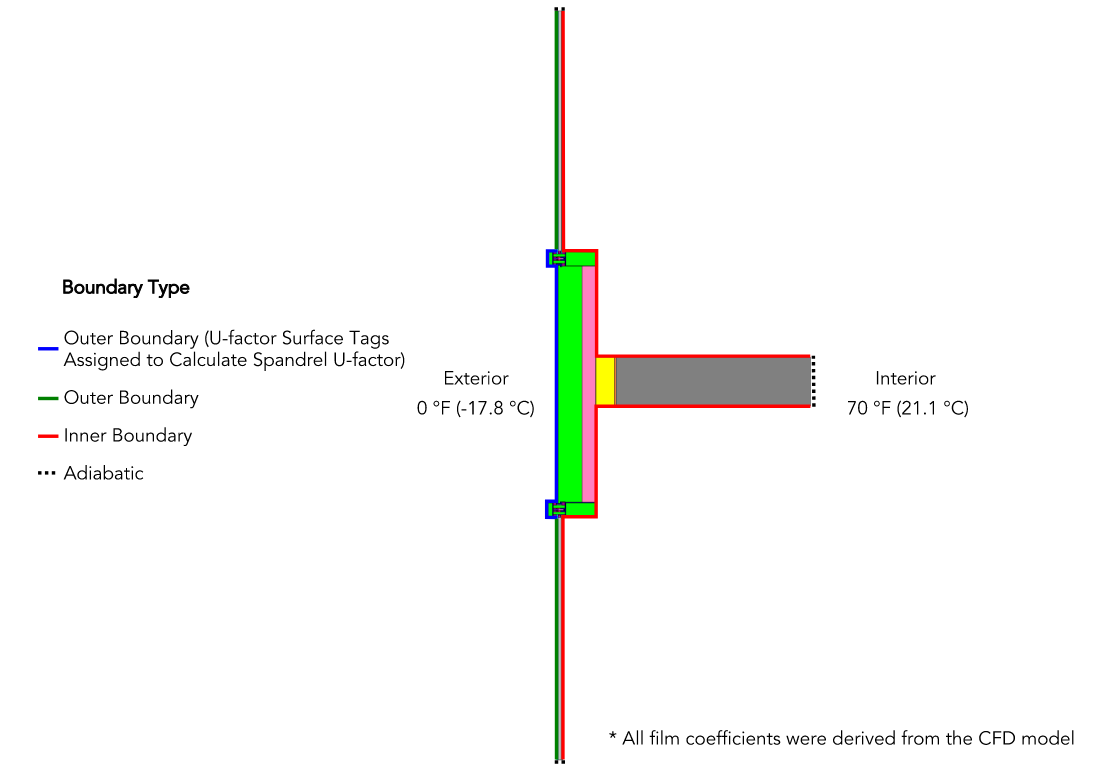

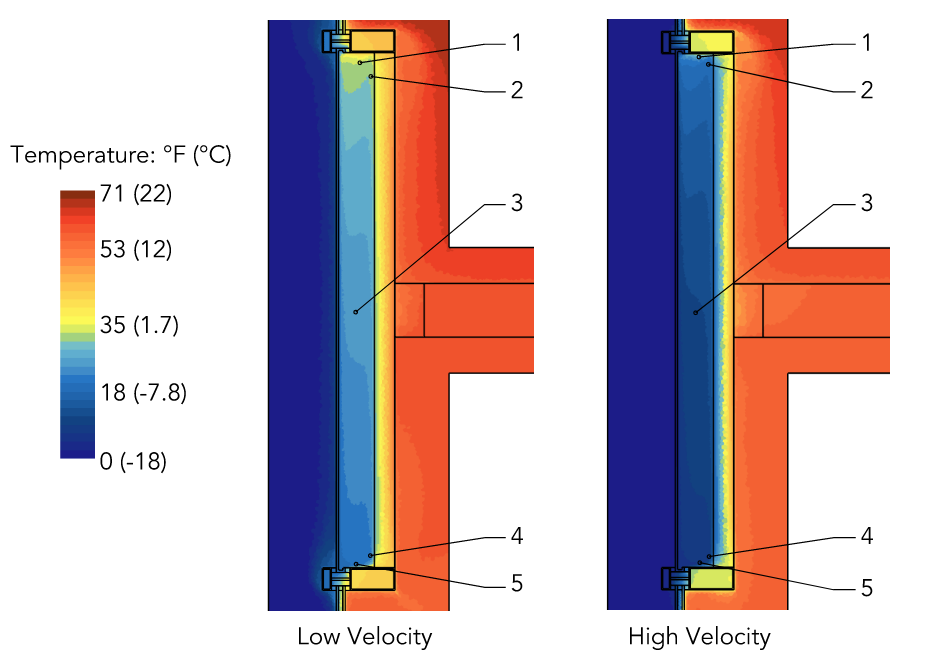

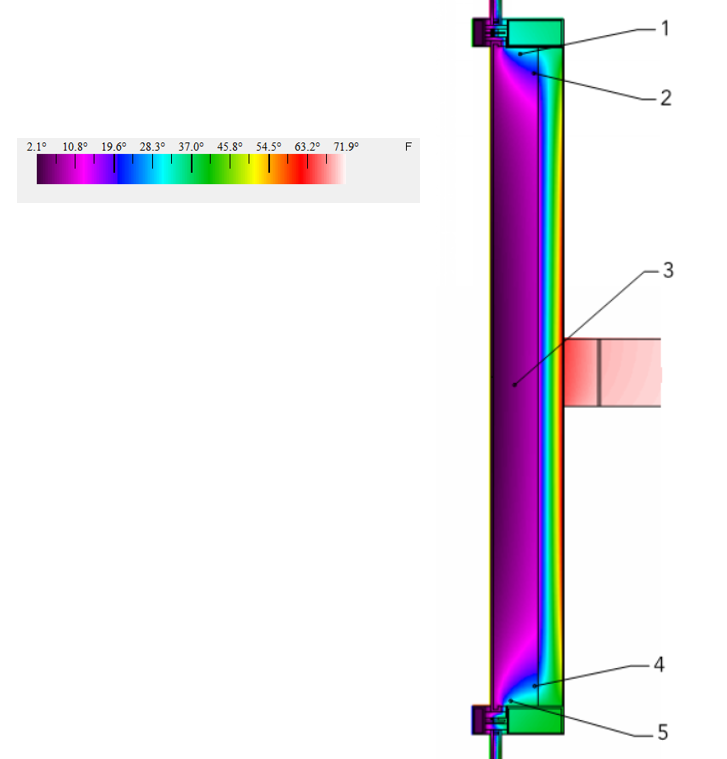

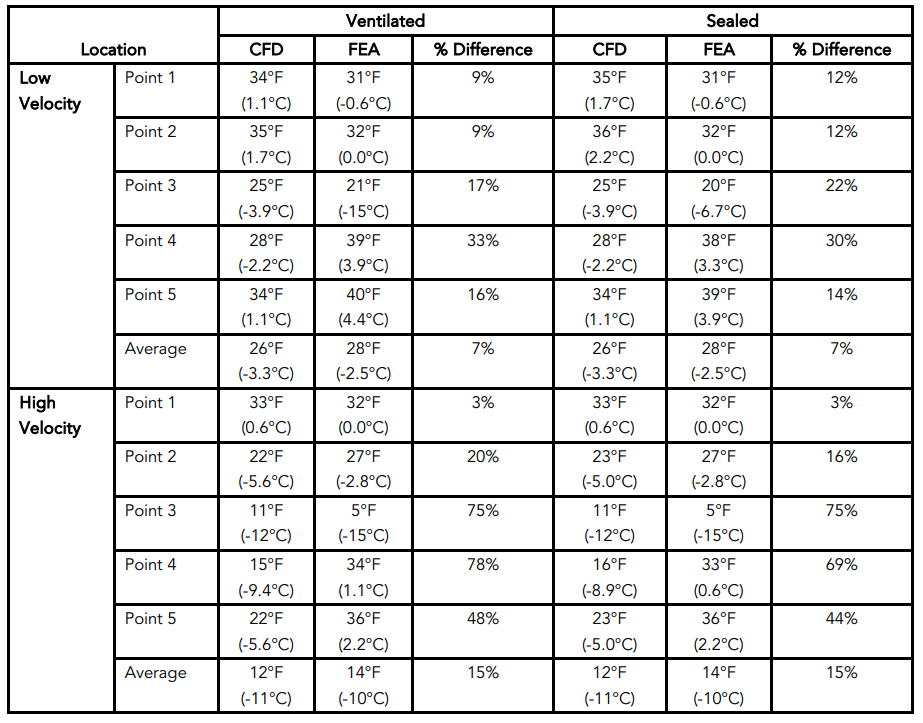

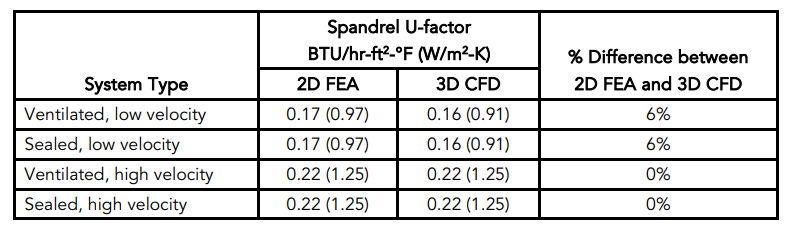

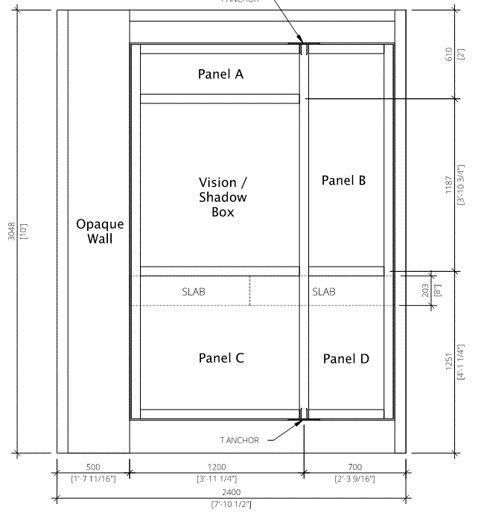

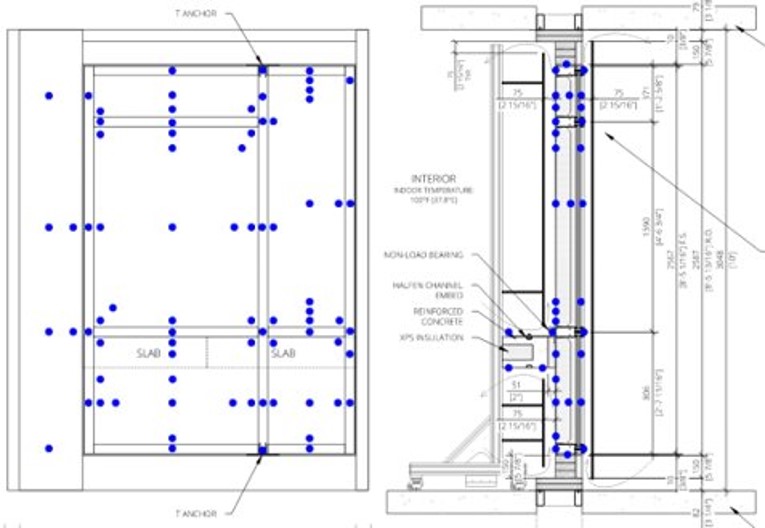

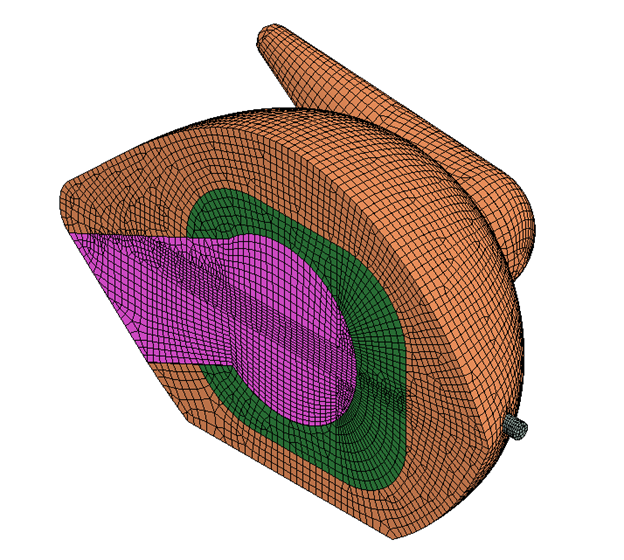

This research project, funded by the Charles Pankow Foundation, is a joint effort by 3 firms (Simpson Gumpertz & Heger, Morrison Hershfield, and RDH) to develop a consistent simulation methodology for evaluating the thermal performance of spandrels in glazing systems. The project employs 2D and 3D simulations and experimental testing with Oak Ridge National Laboratory to study the 2D and 3D heat flow effects often ignored in current calculation methods.