Background

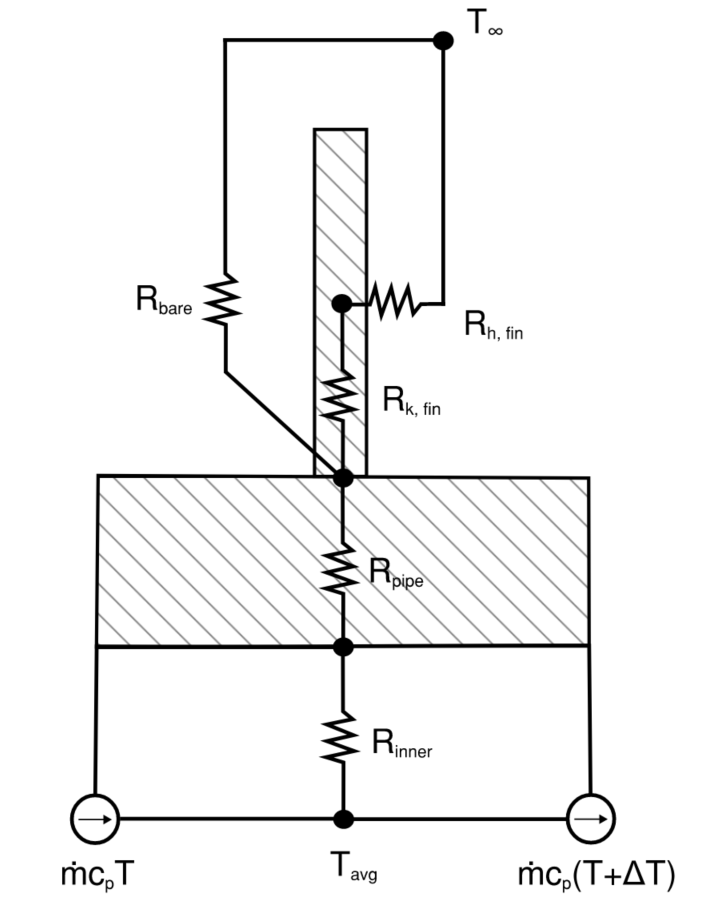

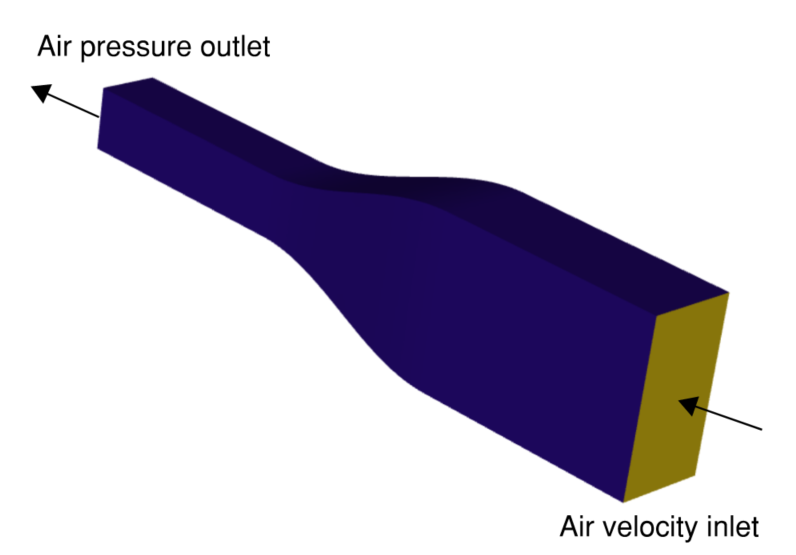

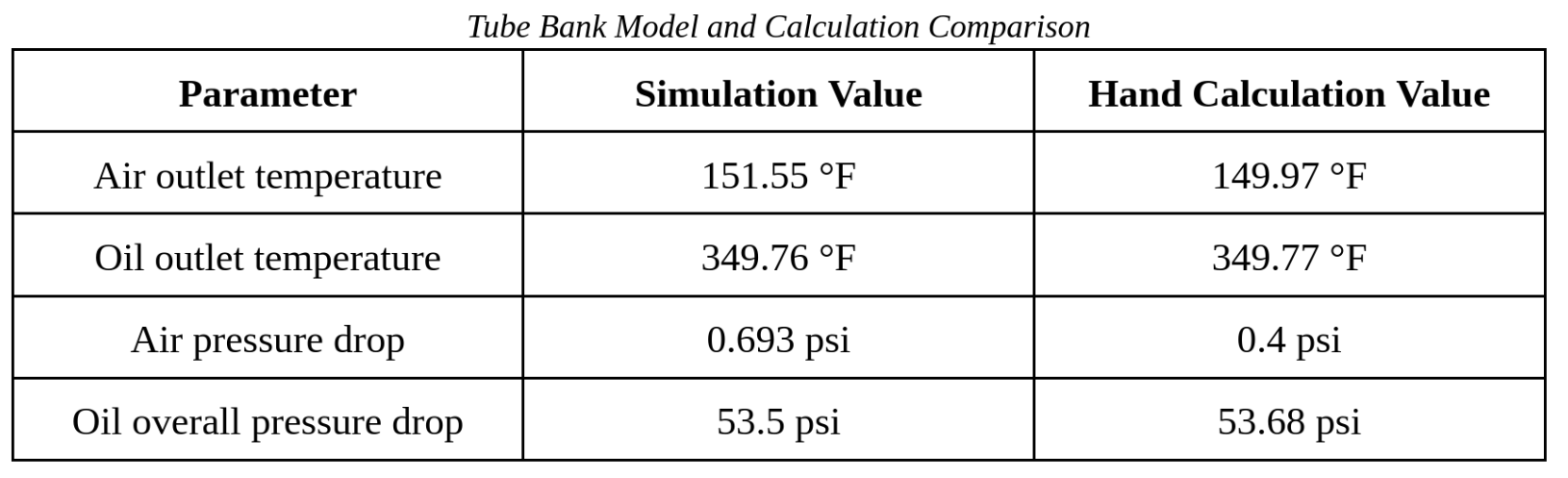

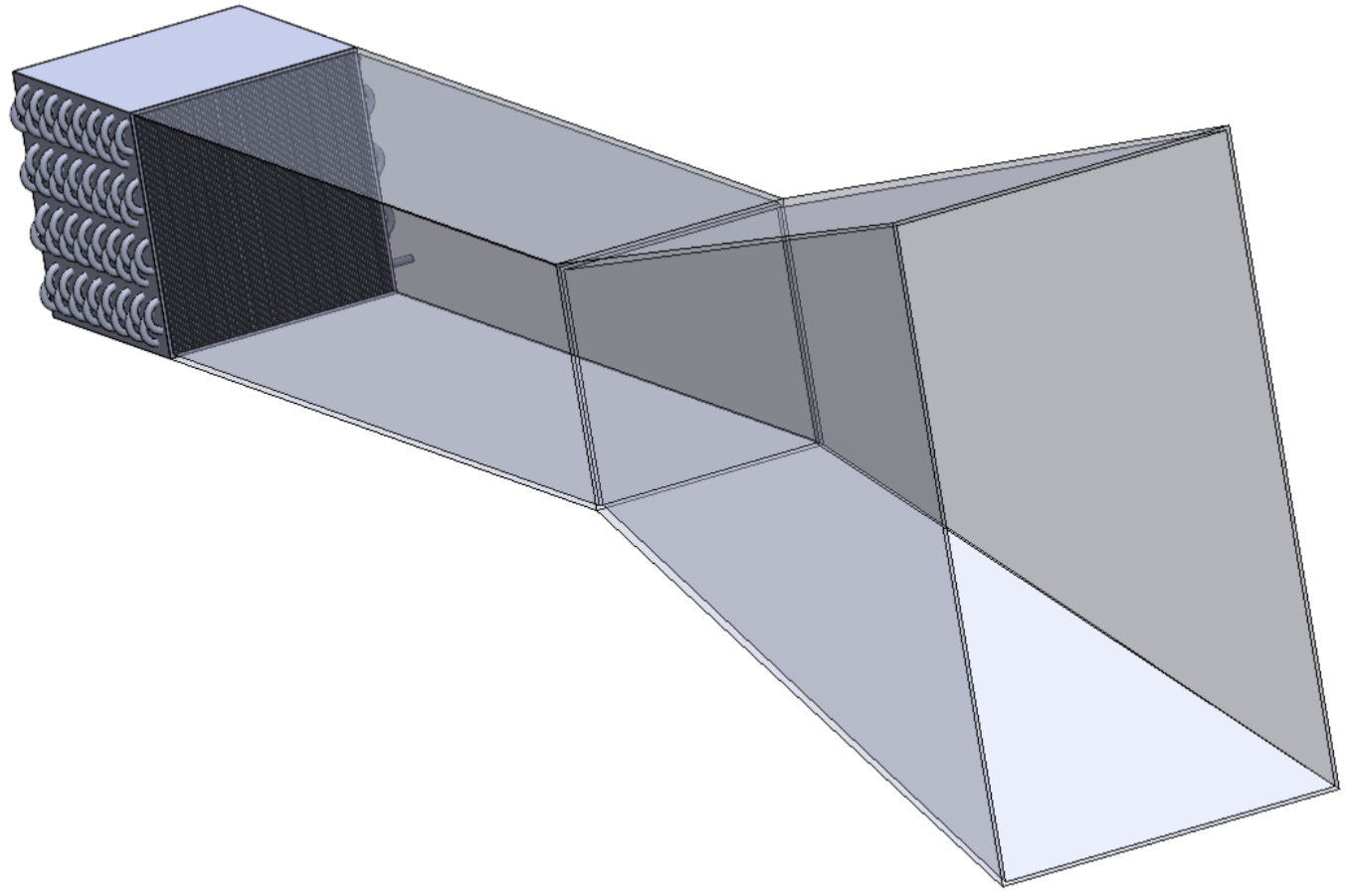

For the midterm project in Cooper Union’s Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) course, the class was divided into 4-person teams tasked with designing an automotive heat exchanger under specified temperature and velocity constraints. The objective was to minimize the size and dry weight of the heat exchanger while reducing the engine oil temperature from 350°F to a maximum of 195°F. The incoming air temperature was 108°F, and the oil flow rate ranged from 3.5 to 5.5 gpm, with the vehicle moving at 25 mph. The air was delivered via a duct mounted 60 inches upstream of the heat exchanger; the design of the duct aside from its inlet area was also to be designed. No constraints are placed on material compatibility or pressure drops for air or oil across the heat exchanger aside from standard engineering assumptions in line with existing automotive heat exchangers. We performed a set of steady-state CFD simulations and validation hand calculations to carry out this design task.

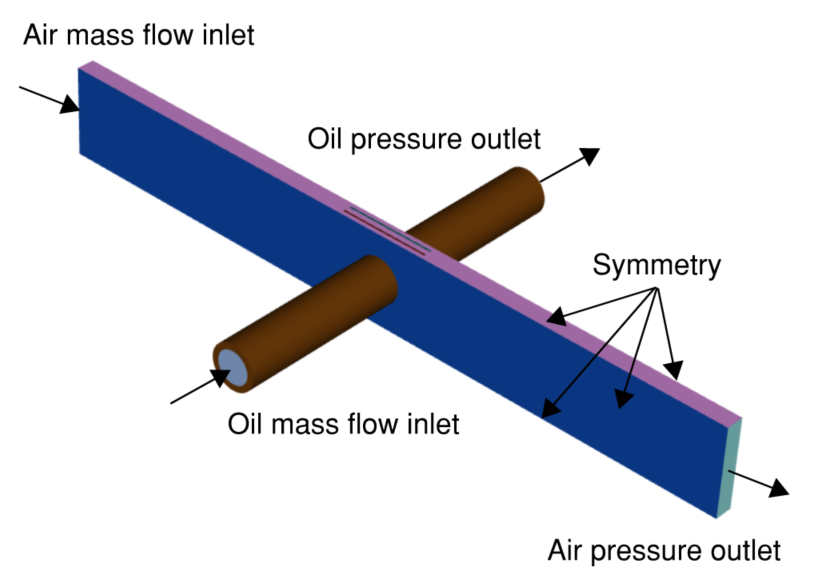

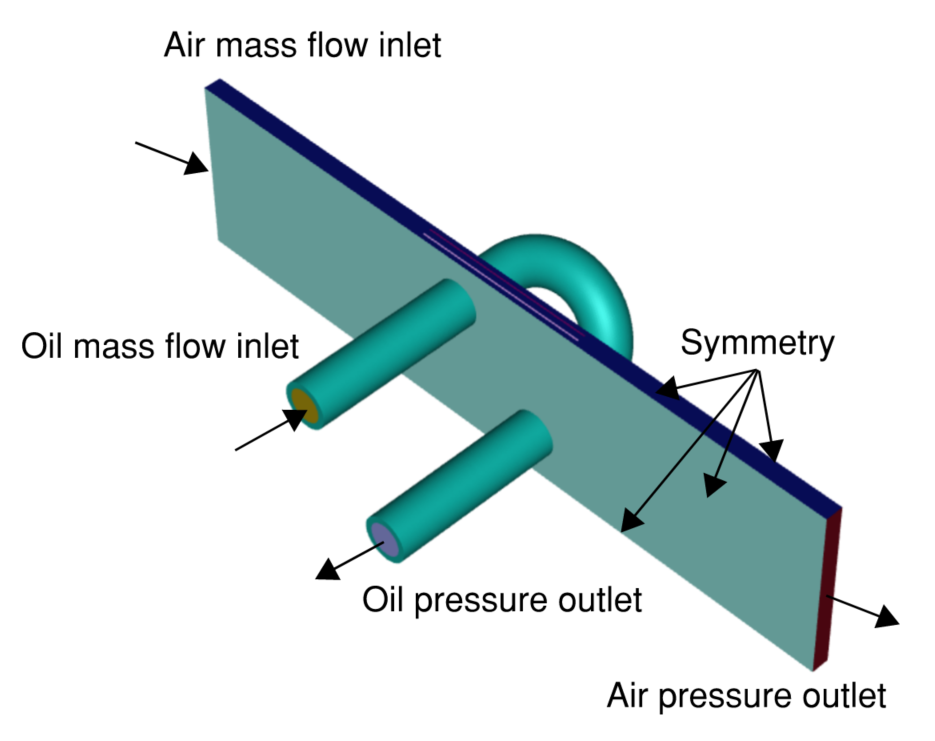

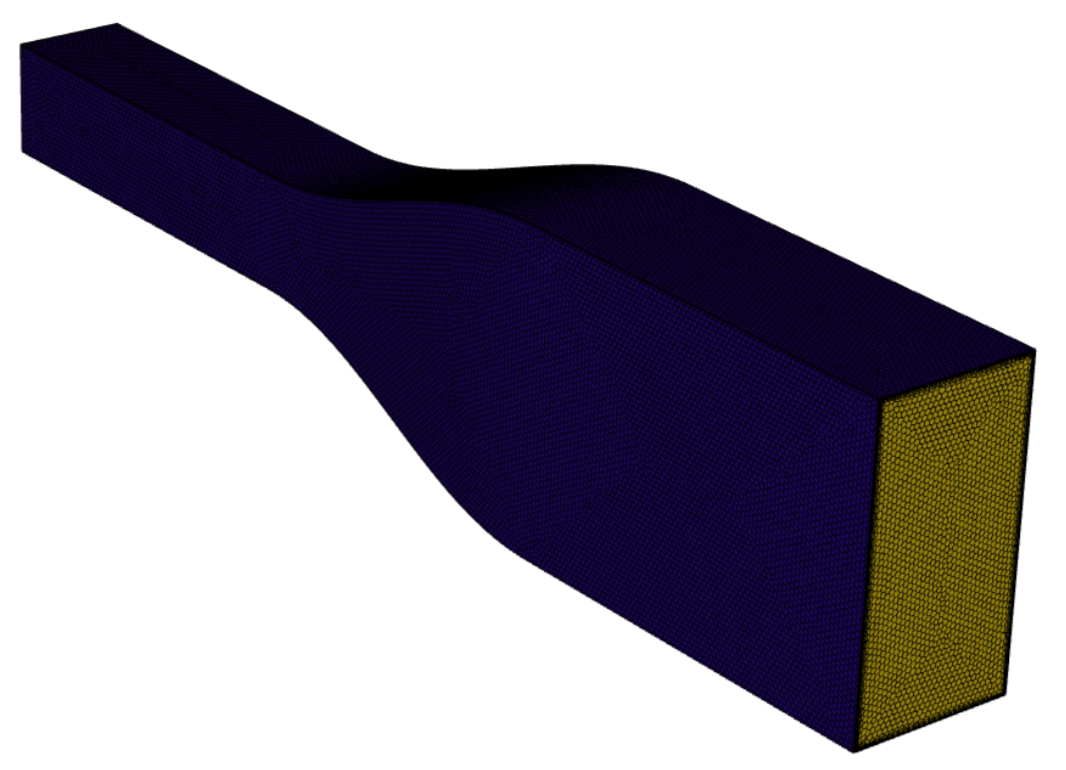

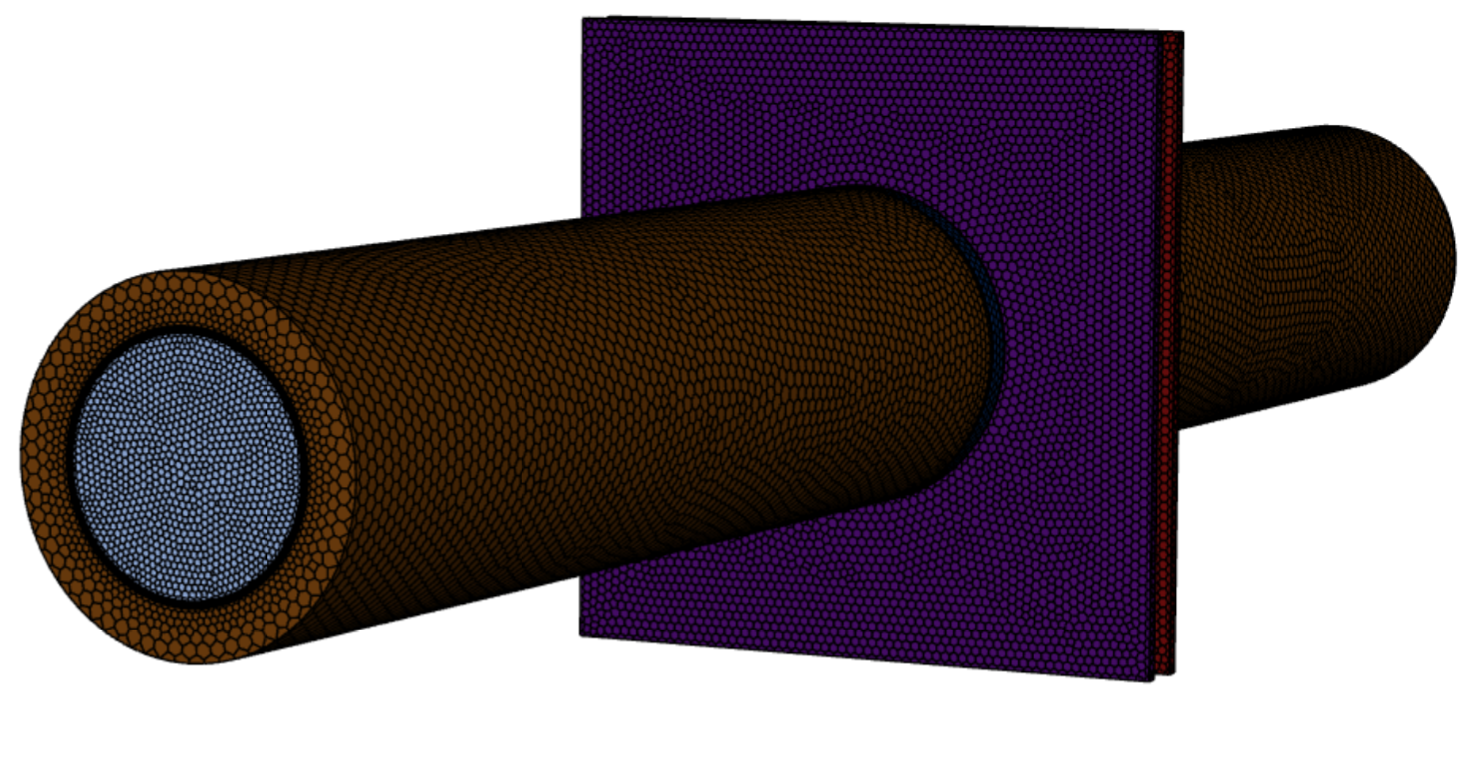

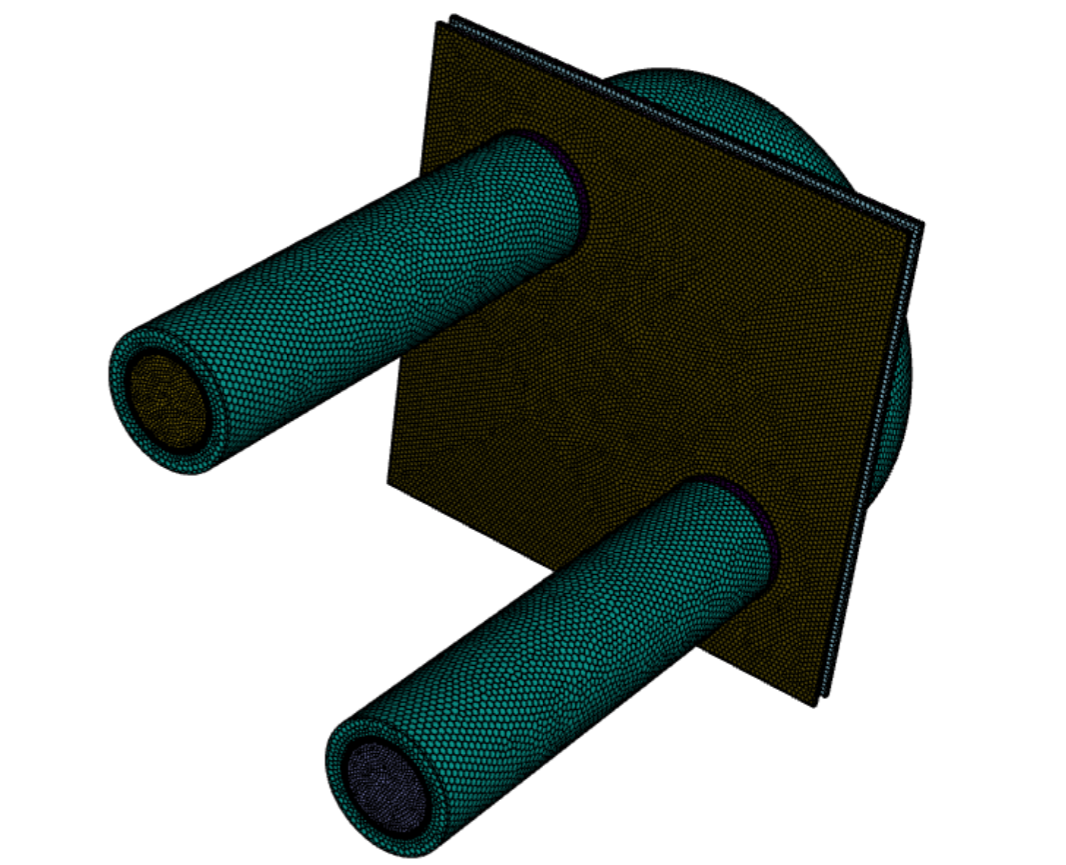

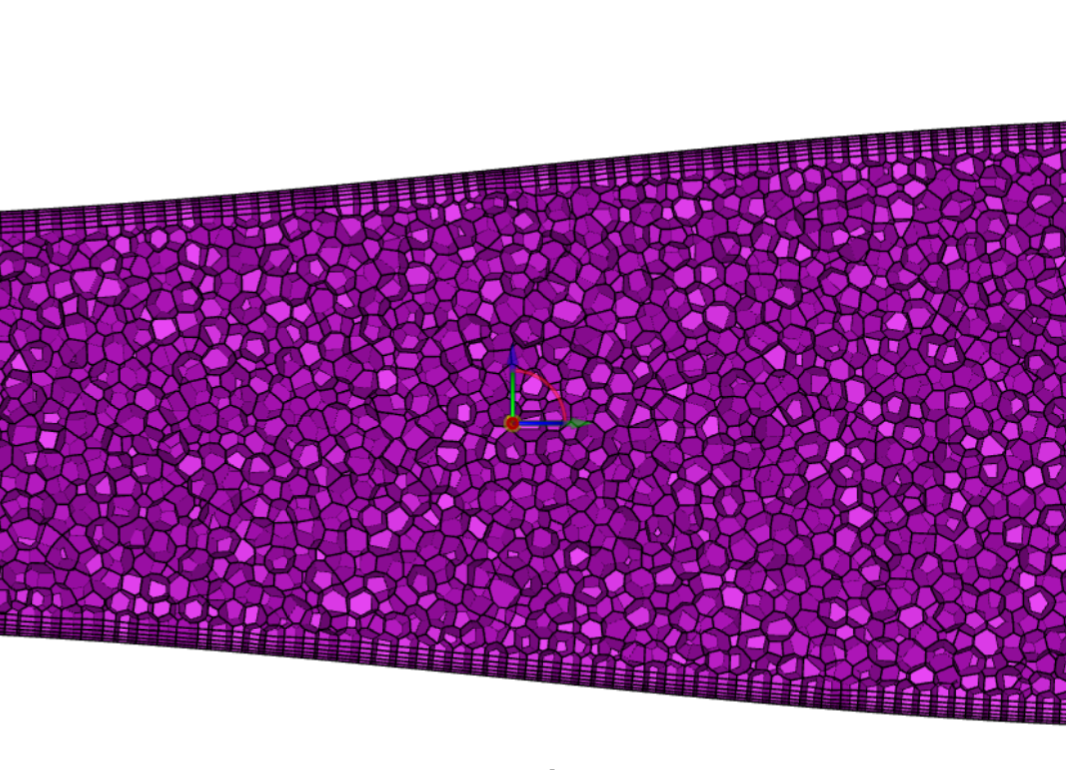

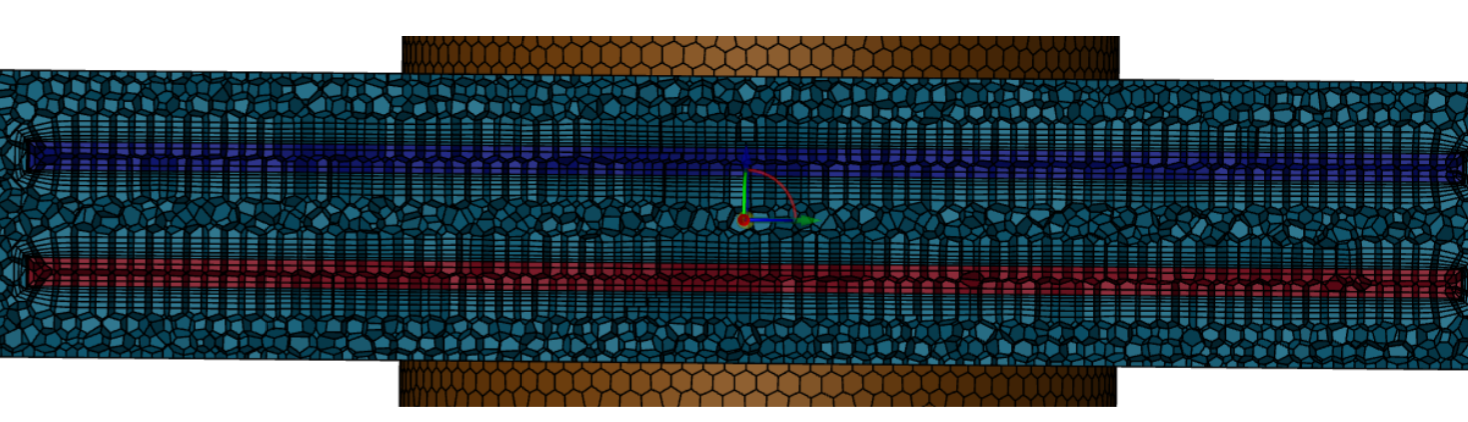

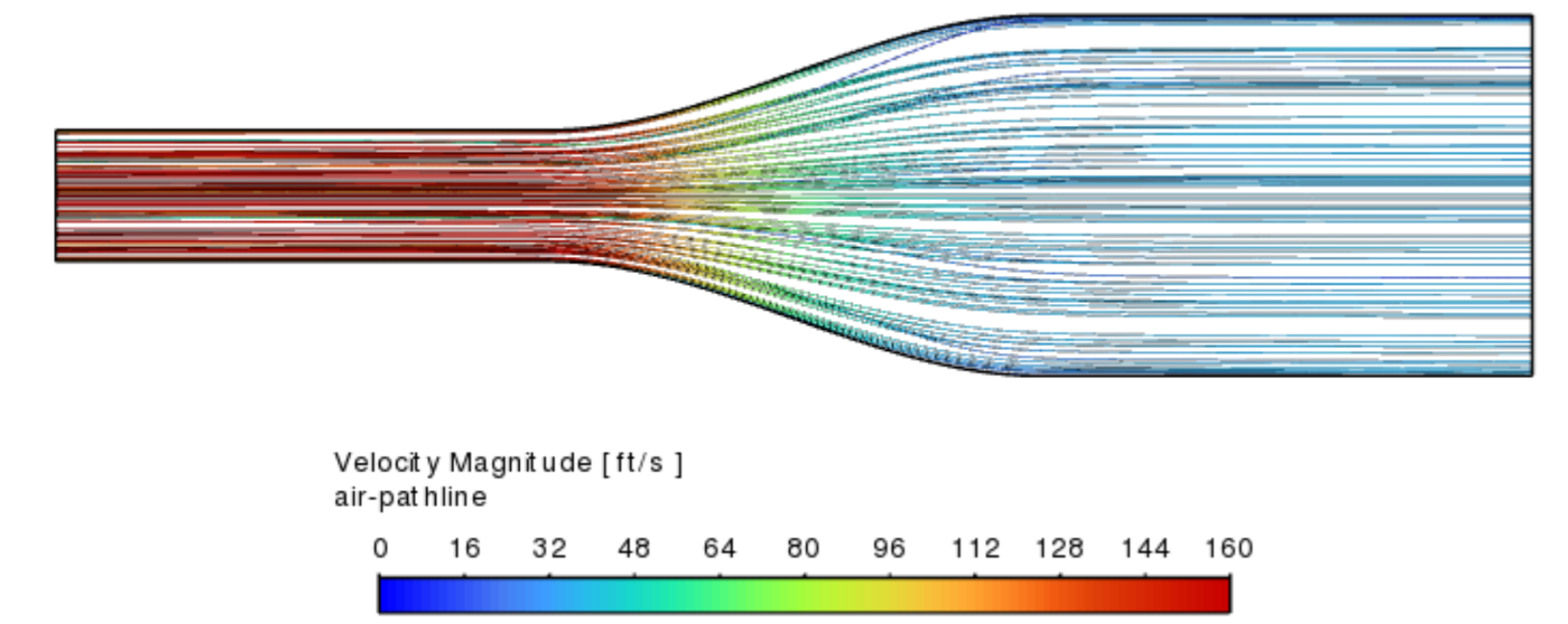

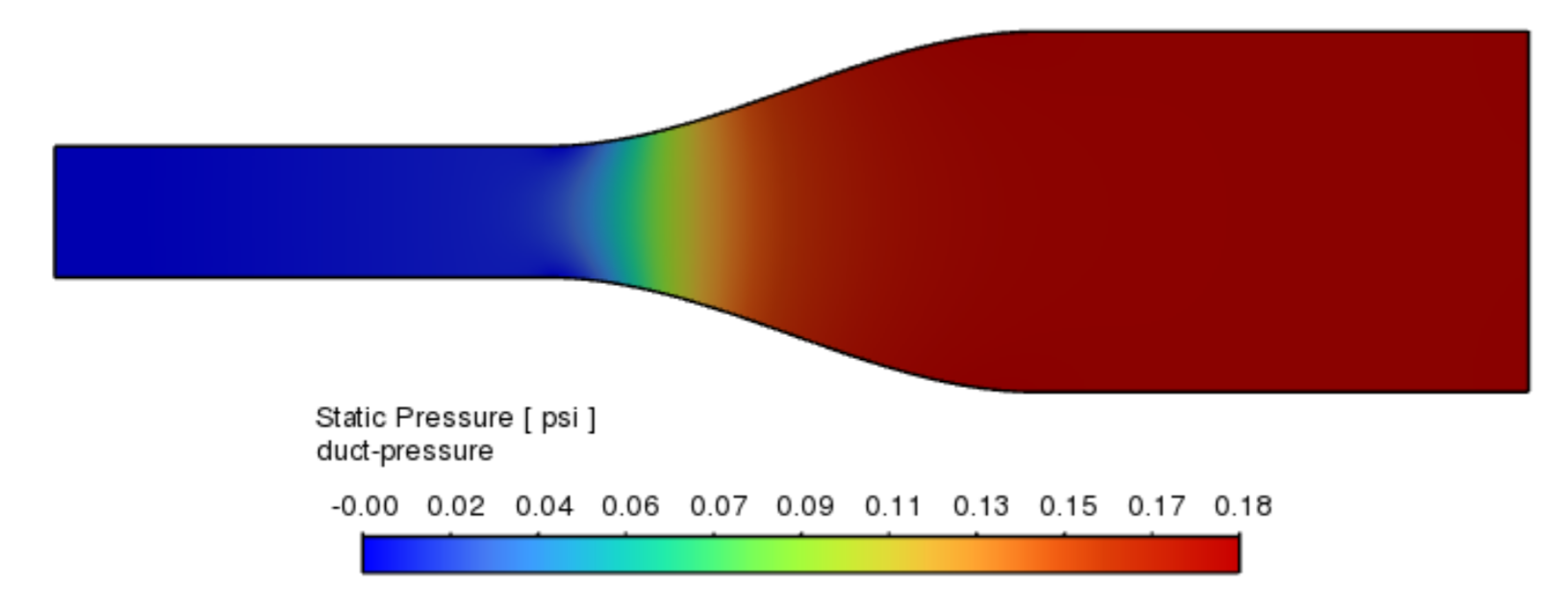

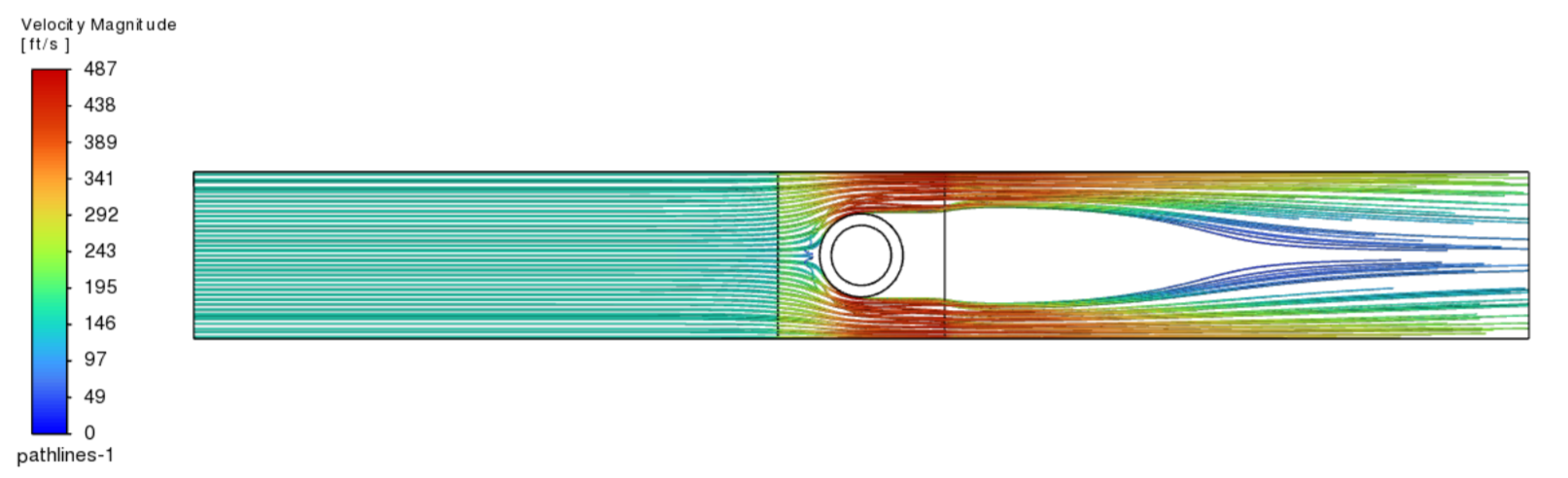

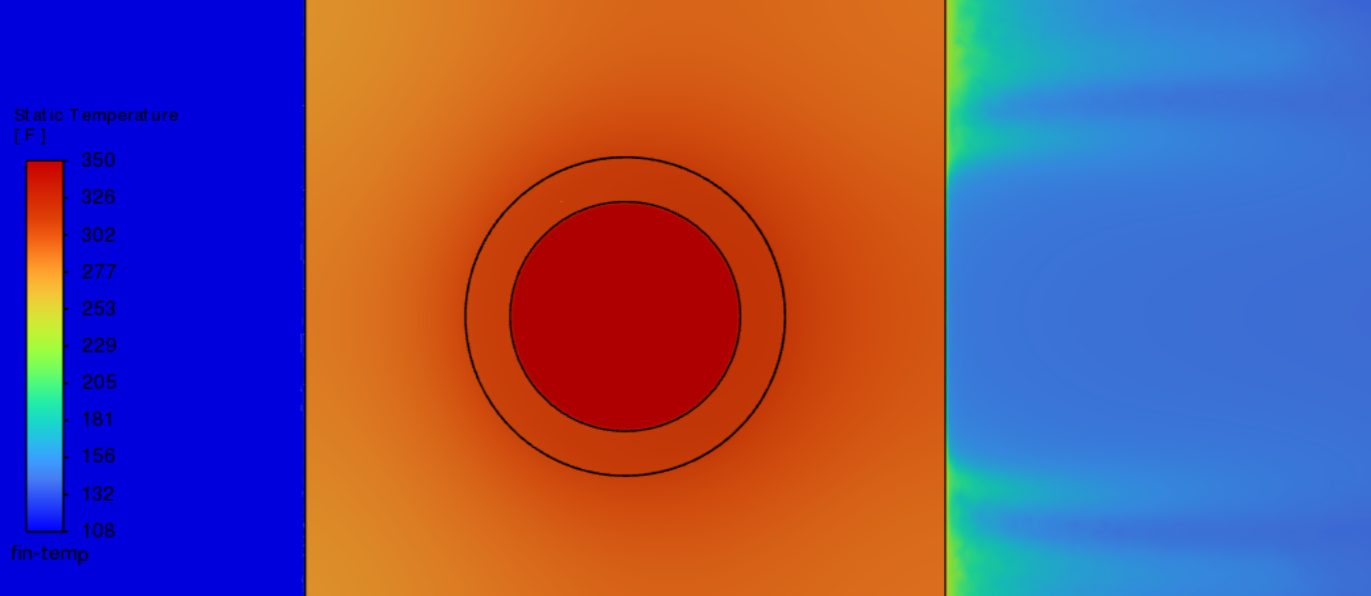

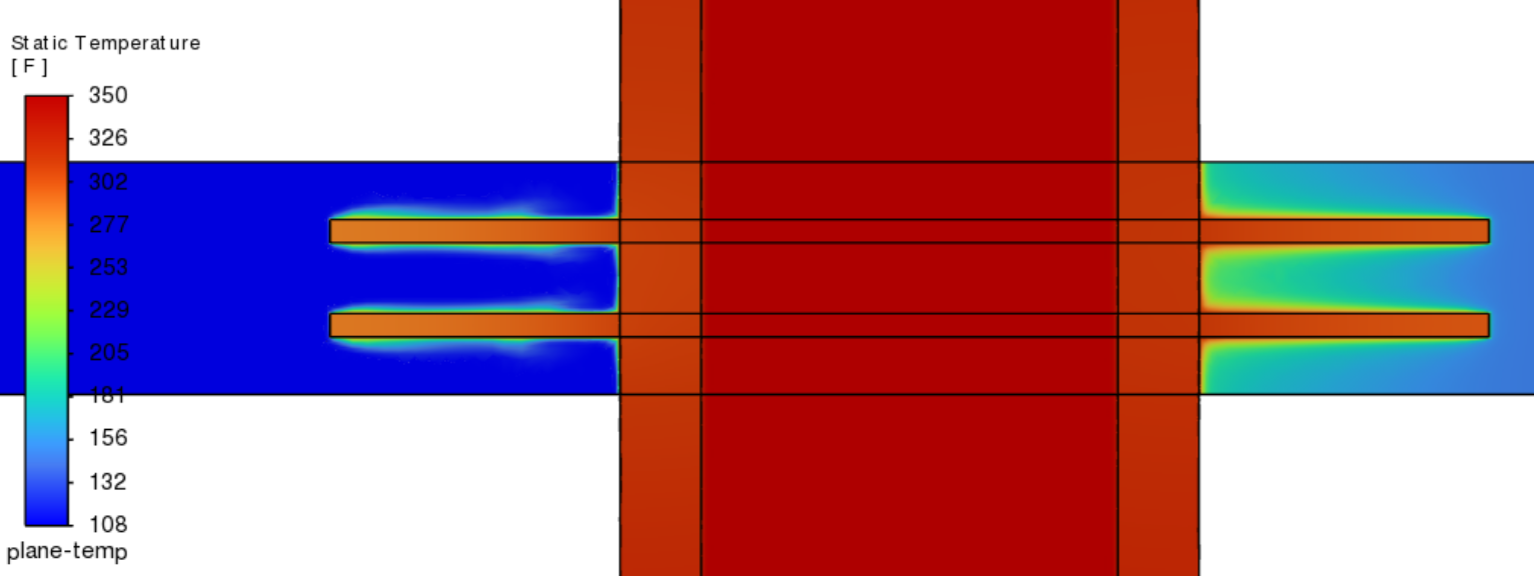

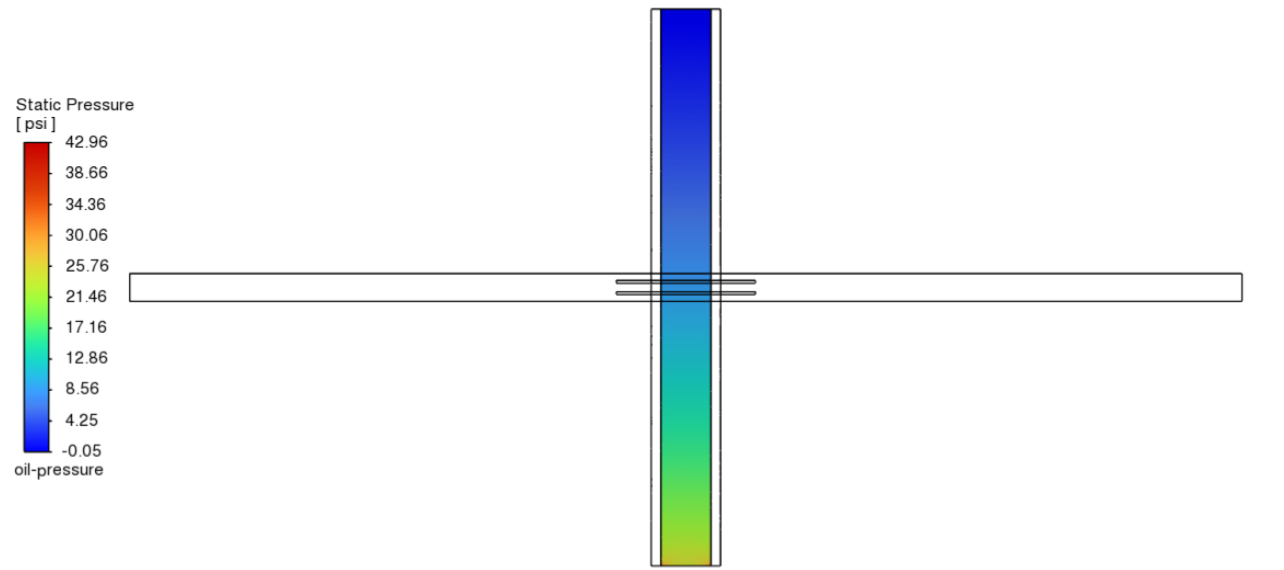

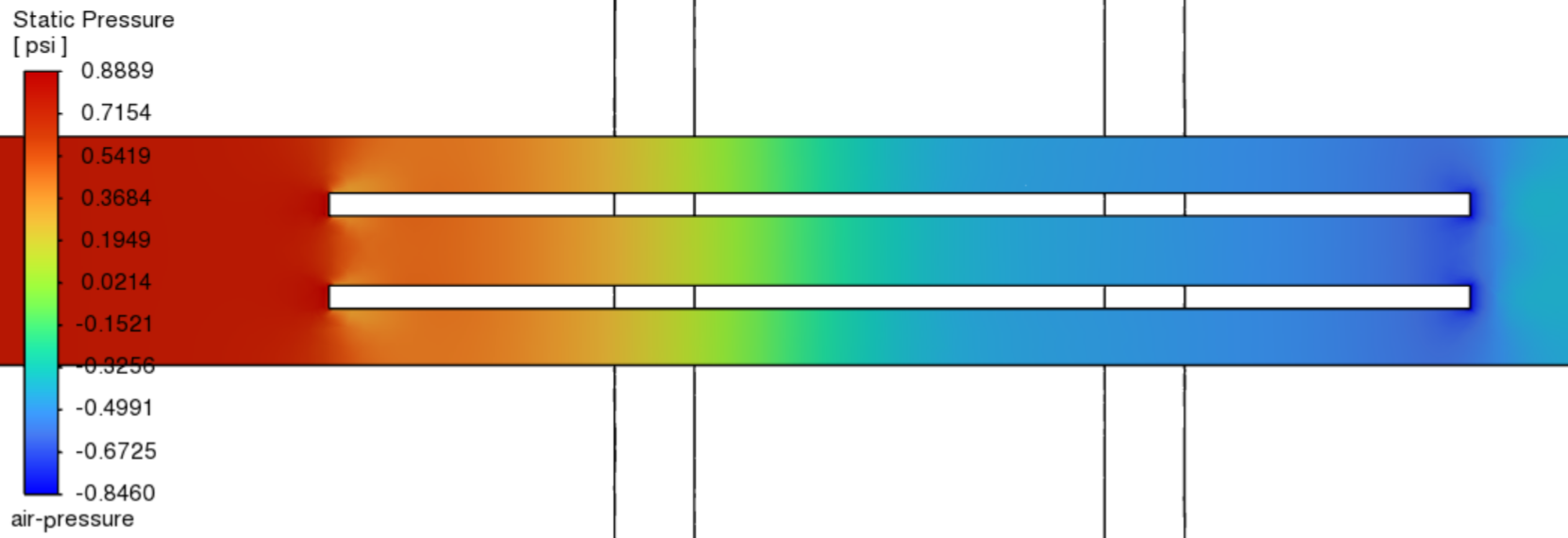

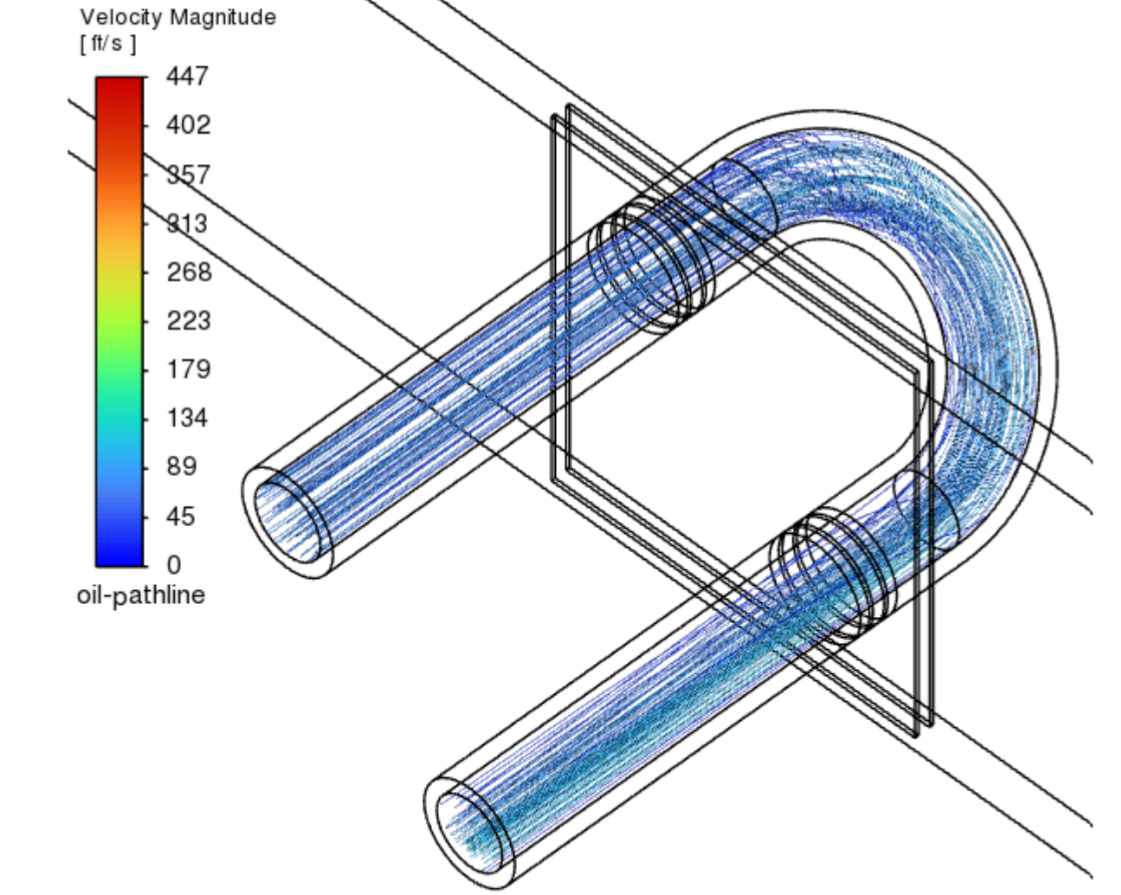

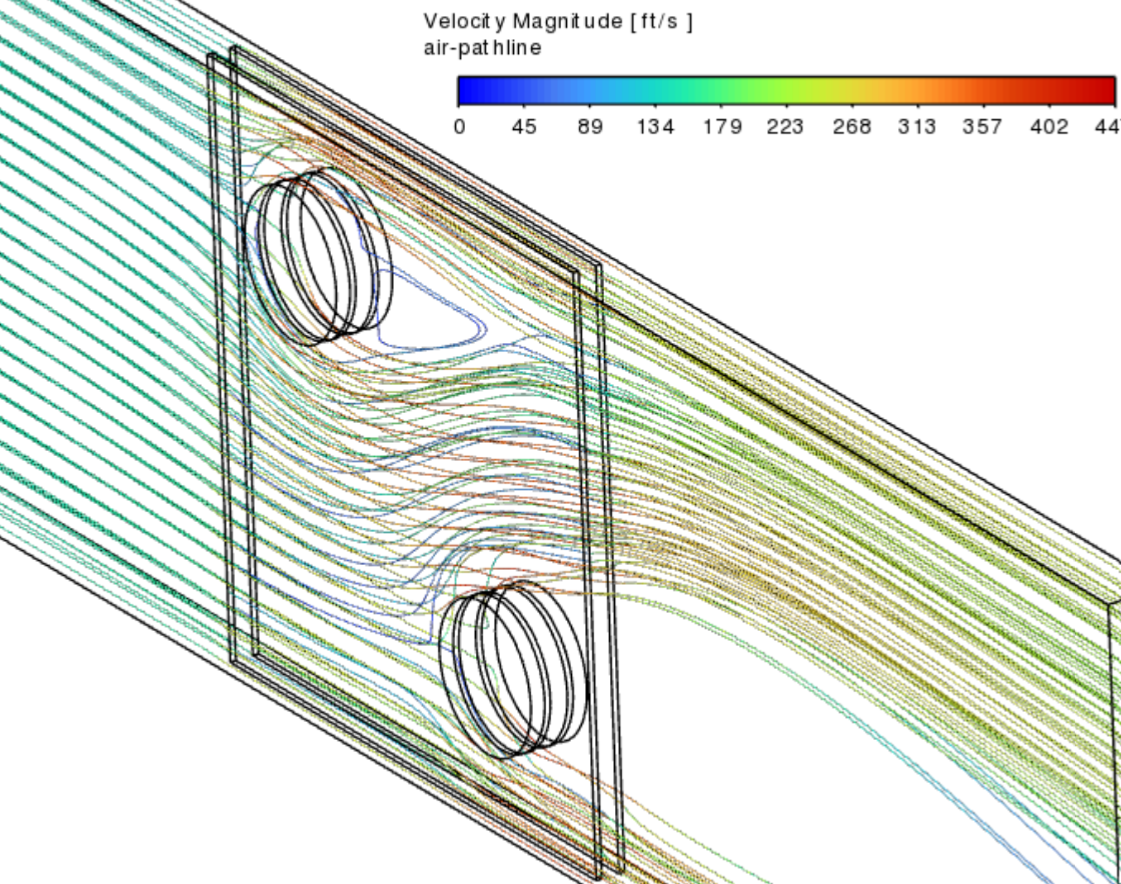

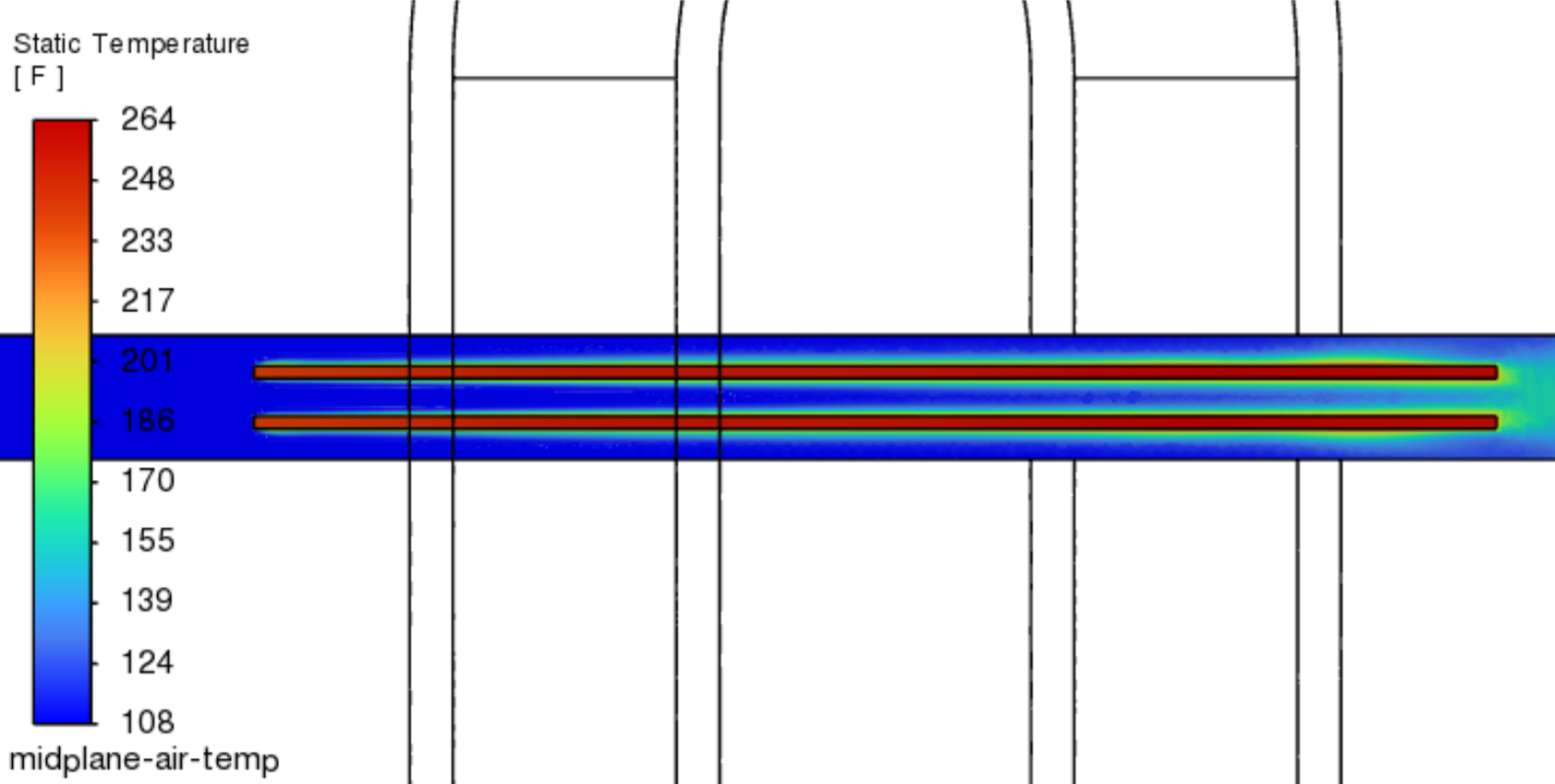

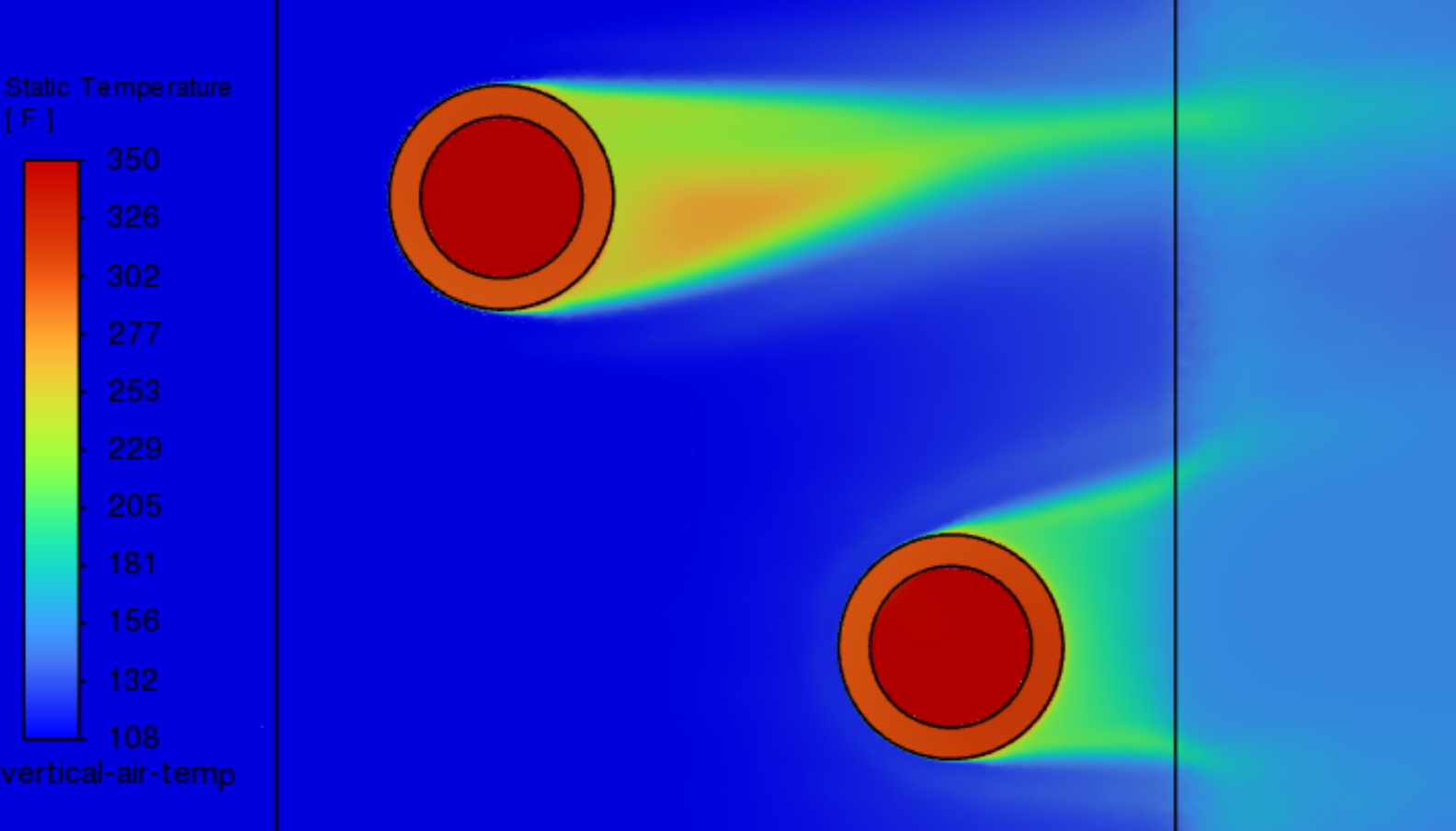

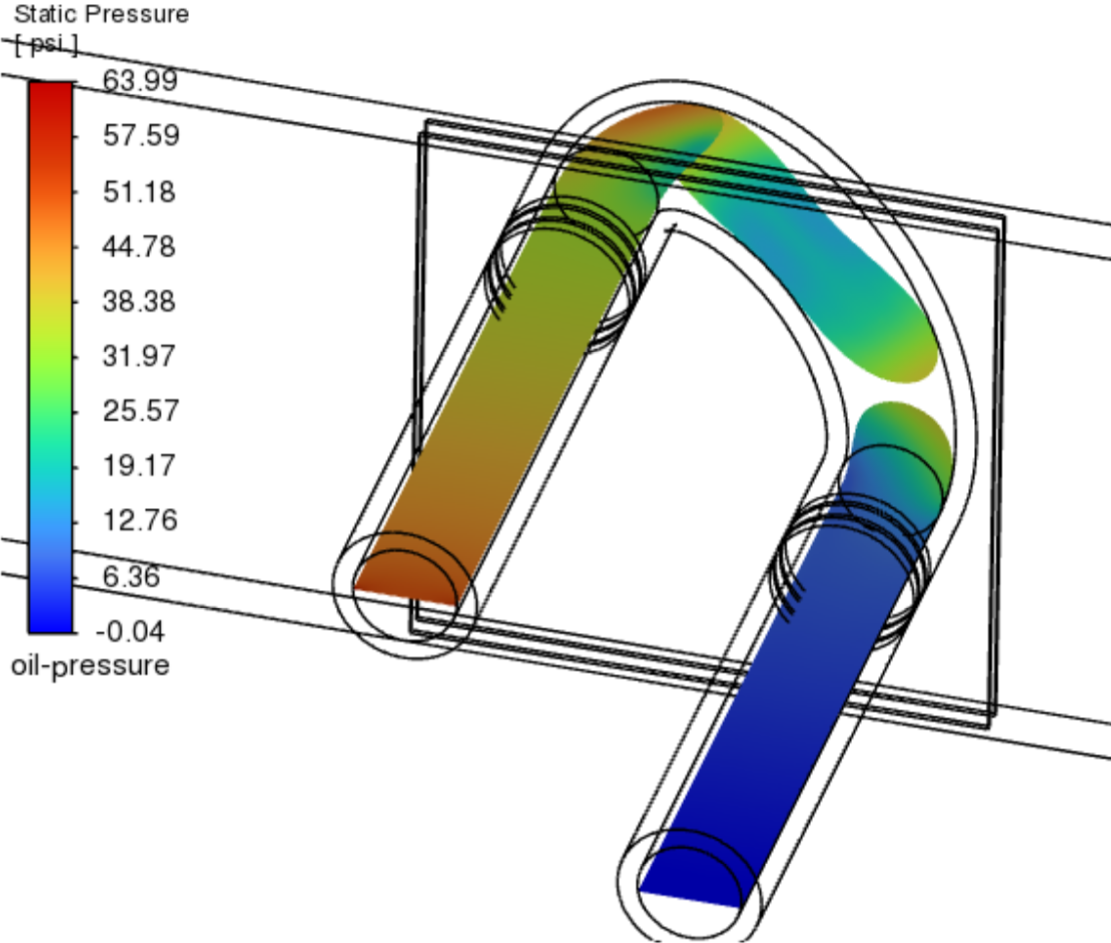

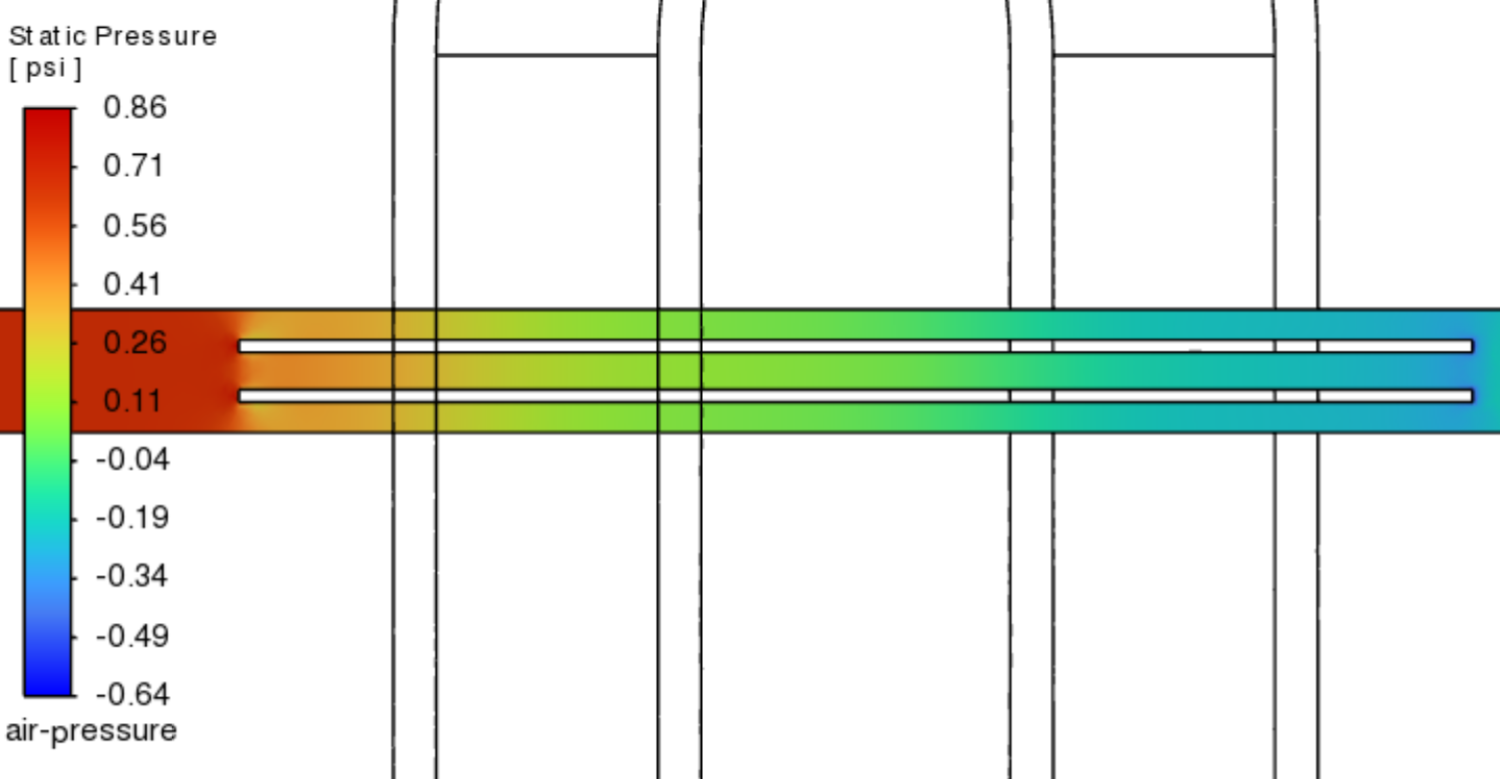

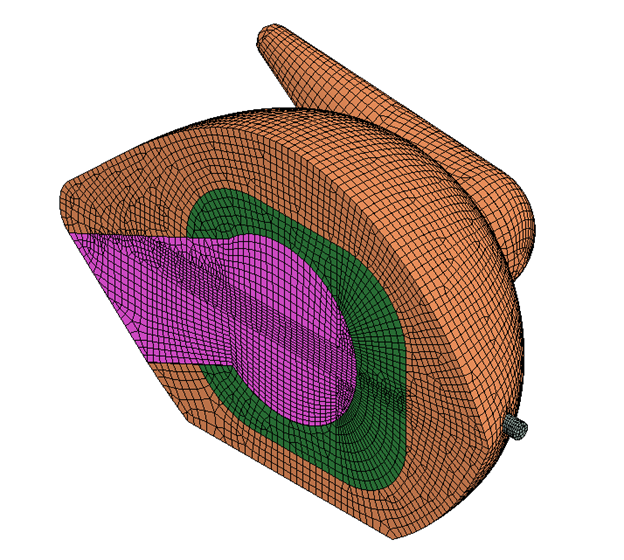

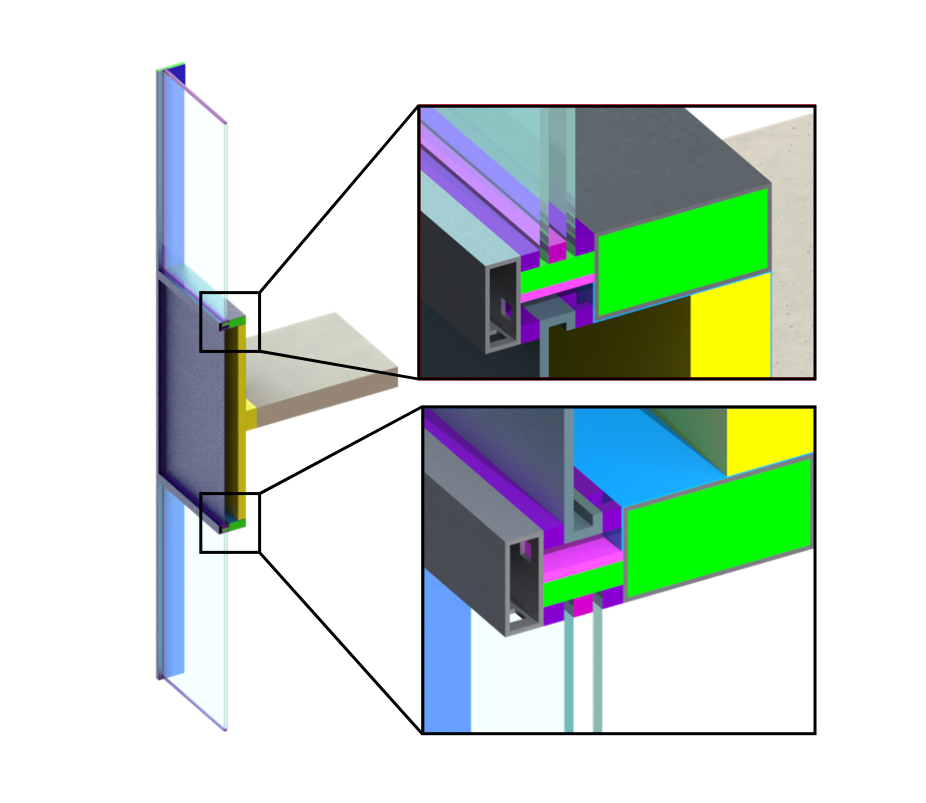

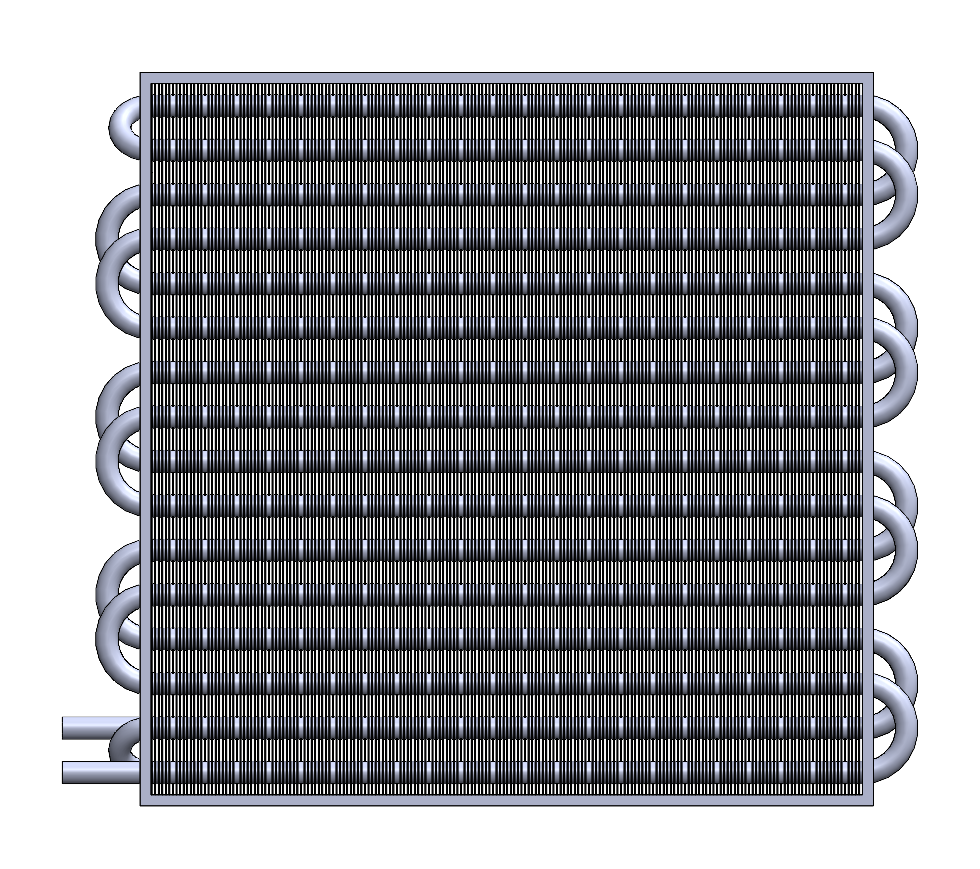

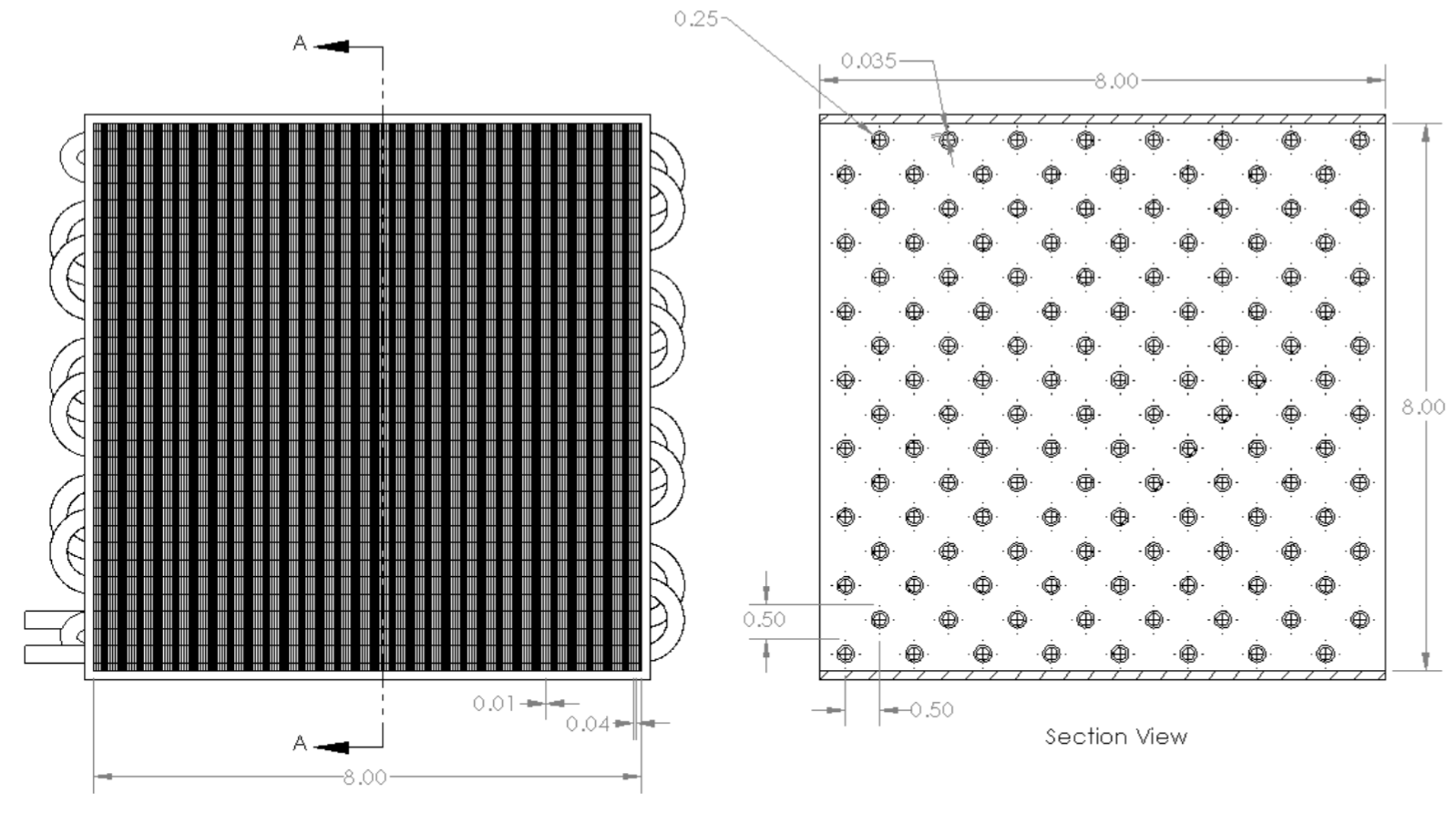

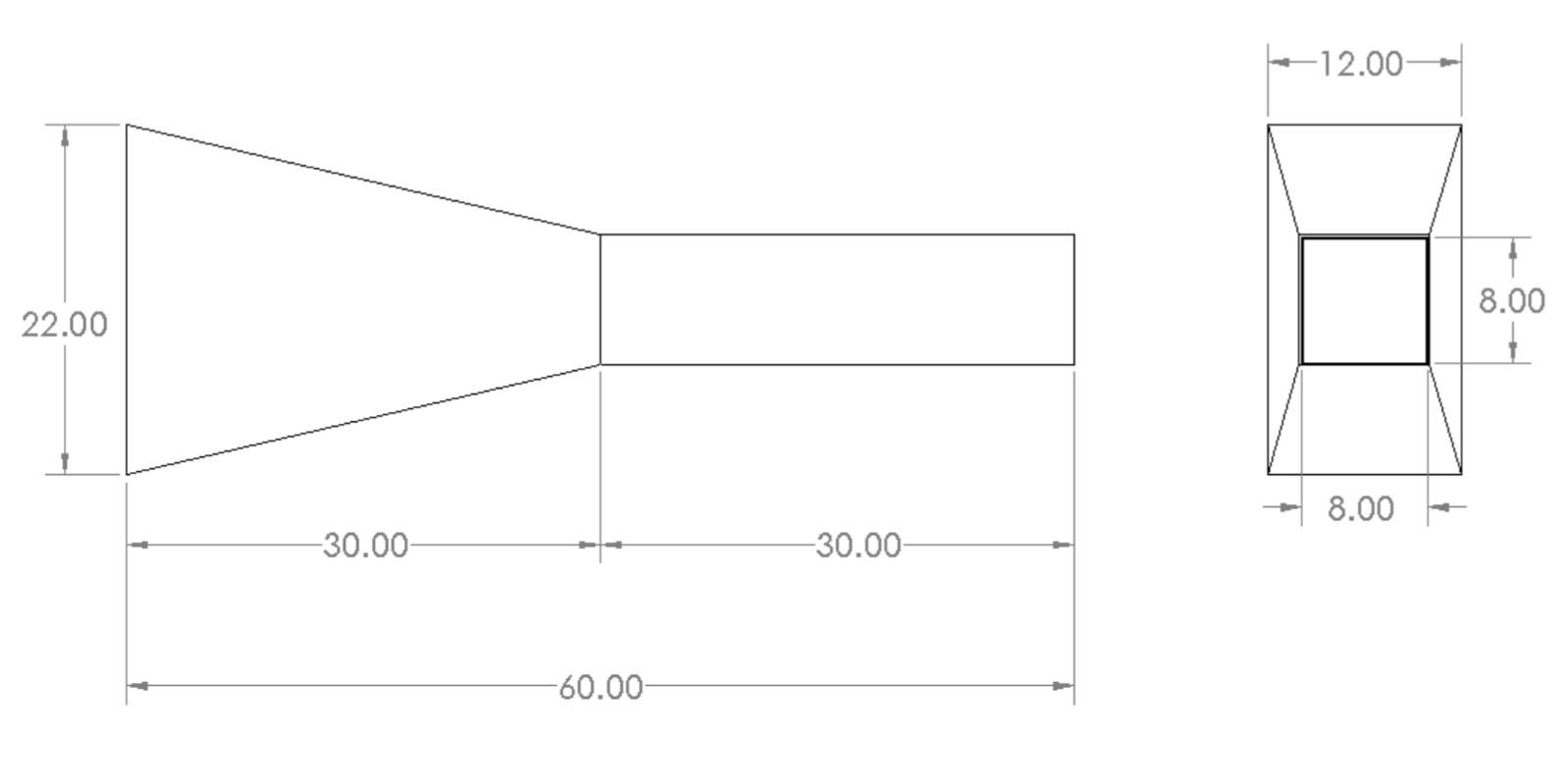

Heat exchanger simplified geometry.

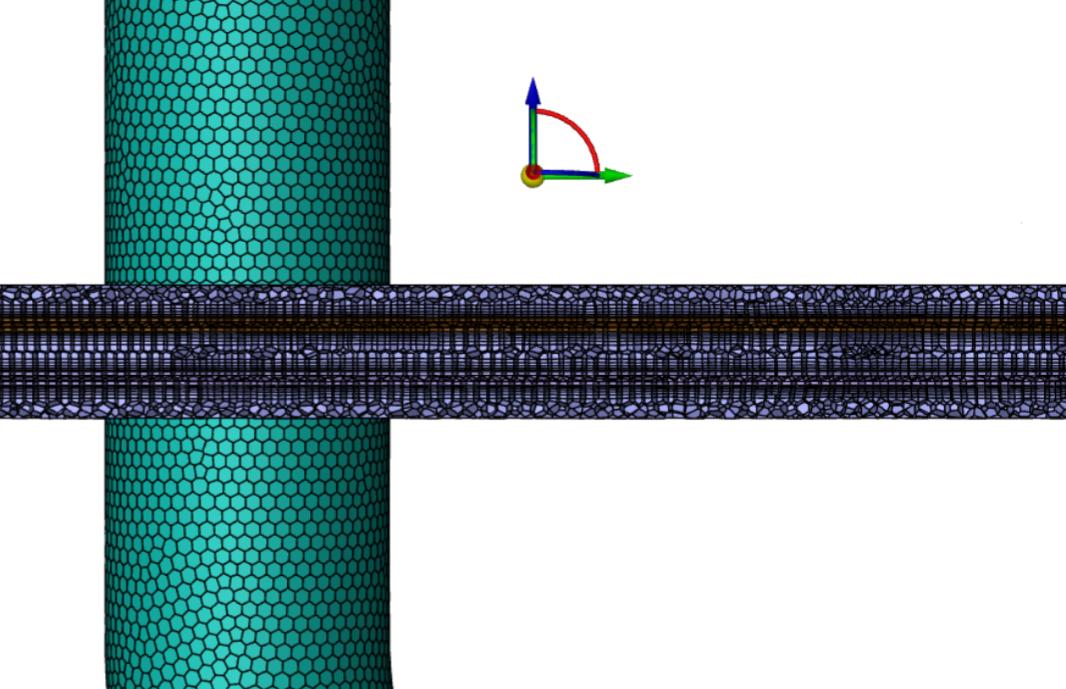

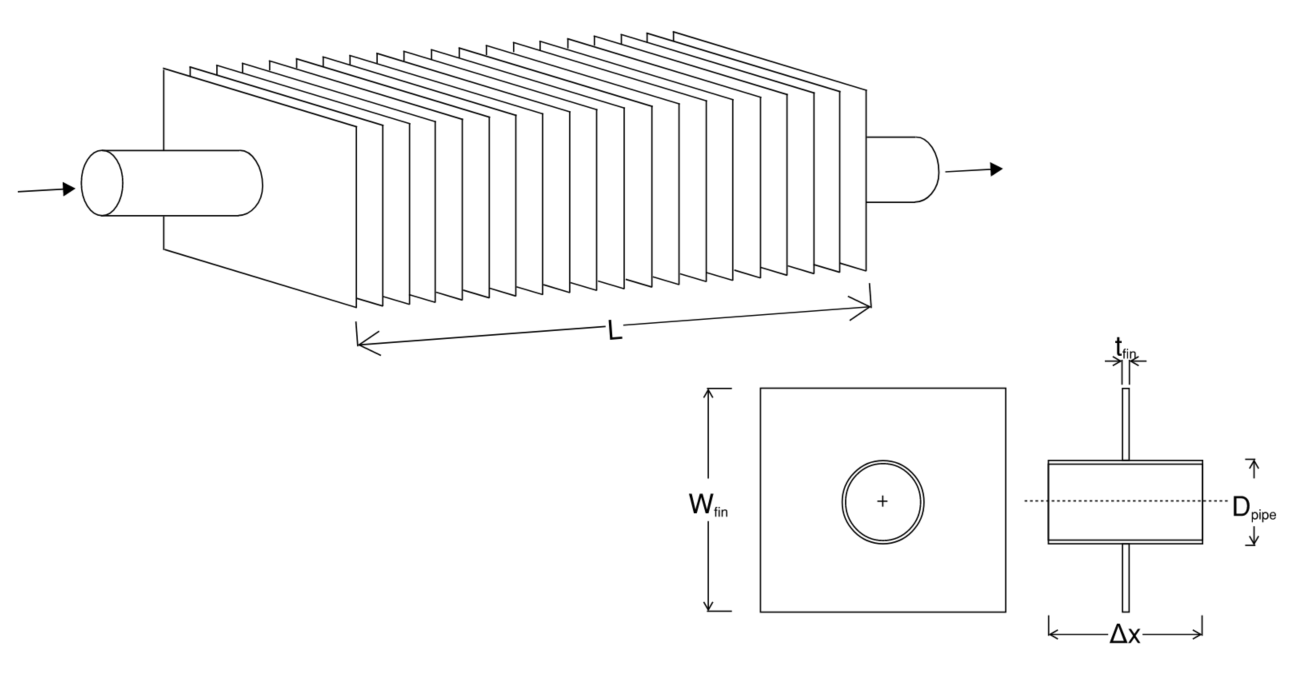

Heat exchanger simplified geometry.